I’m not asking you

to hold me together.

I’m asking you

to open so wide

there’s room for all the ways

I come apart.

—James A. Pearson, “How to Listen”

Everyone wants to be strong these days. Peri-menopausal women, post-menopausal women. Teenage women, post-partum women. All the women. And, of course, all the men, as has been the cultural norm forever and always. This shift in attention to strength, and away from the cardio-crazed super-skinny aesthetic my generation grew up with, has prompted a ripple of associated conversations on the “right way” to build strength. How many reps and sets. To lift heavy or to HIIT. Protein—all the time, your body weight’s worth of protein, plants and animals and man-made.

Whether you’re participating in this strength moment, actively resisting it, or somewhere in the middle—like me—navigating these swings in fitness and health trends can sometimes feel like a full-time job. You need totally different equipment, memberships, outfits, and schedules to accommodate a run (all you need is you, and it can easily be free) versus a heavy-lift (you’ll probably want a trainer to show you what you’re doing, and you’ll need heavy things to lift and a place to do it). But even more than these material aspects, it isn’t easy to adopt a different way of feeling, seeing, and moving in your body. Though yoga and other mindfulness practices reminds us that we are not our bodies, that adage is somewhat incomplete—our entire identity is not limited to our physical body, yet it’s our home for now and our sense of self is inevitably tied to this miraculous, and frustrating, heap of cells and tissues. Each extreme diet or lifestyle regimen comes with a radically different set of sensations, physiological processes and side-effects, and energetic outcomes that change the lens through which you see the world and yourself in it. When you go to the grocery store, do your eyes filter out all the carbs so you only see veggies and protein? Are you compulsively drawn to the supplements aisle? Do your movement and food diets reinforce speed and lightness, or stability and density?

These factors aren’t usually included in the IG captions and 75 Hard Challenge guidelines—if the requirements of these trends weren’t hard enough, embarking on an identity makeover might not garner thousands of likes and sign-ups. Rather, they’re the language of Ayurveda, which assesses all of our stimuli according to their qualities, or gunas, and their actions, or karmas, on our physical, energetic, and mental bodies; this includes the twenty gunas of the material world, and the three gunas of the mind, known as mahagunas (sattva, rajas, and tamas). The amount of effort you need to put into the new routine will depend on your baseline going into it—if your constitution is already pretty robust, then adopting strength training might feel natural and you might not see a huge change; on the other hand, a person with a lighter frame might need more external supports and have a longer timeline for building strength. When regimens presented to the general public don’t take these considerations into account, followers’ faith and success can be tested if they don’t fall into the one-size-fits-all formula for getting a new body in a few months.

I yielded to strength a few years ago. Up until then, I thrived on a combination of yoga, Pilates, and running, and was proud that I could carry a full box of hardcover books (~15-20 pounds) around my office in three-inch heels with more ease than the handful of male assistants could. Or, I thought I was thriving on that movement diet. As much as I enjoyed those activities, I always had a little tweak or injury going on around which I’d have to adjust my practices. In a certain way, these challenges opened me up to a variety of therapeutic movements that I’ve been able to use more nimbly over time, and share with students and clients. But without a basis of strength, I was constantly pushing up against and just over my edge, then having to rehab myself back to “normal.”

Enter strength. A friend of mine convinced me to try the online classes one of our shared teachers was offering during COVID quarantine. I ordered myself some weights and set them up in an unobtrusive corner of my space, unsure if they’d be a permanent addition to my growing supply of at-home yoga props. On the first morning when I logged into the online video portal instead of lacing up my sneakers for a run, I took a deep breath and reminded myself this wasn’t a marriage or anything binding—it was just a workout. Why was I so nervous about exercise, which I’d been doing pretty much all my life in formal and informal ways? Movement is ingrained in my identity, a benchmark of creative highs and psychological lows. Finding a healthy relationship with this part of myself has been one of the constants of my healing journey, and one of the most tenacious since even when I moved in ways that didn’t serve my health, I could never give it up cold-turkey. Instead, I’ve had to employ my Ayurvedic metrics of guna and karma to create a movement diet that was satisfying for my whole system.

When the dumbbells arrived in my space, and this new event arrived on my calendar, their gunas struck me as a threat. Heavy, dense, and still—all things that were very much not me. The identity that had formed out of my past movements was light, agile, and restless—the embodiment of physical dosha of vata (air and ether) and the mental dosha (mahaguna) known as rajas. Even when I shifted the scales slightly toward more rhythmic and steady movement—say, from running to yoga—on the whole I was not used to the feeling of extra weight on or inside my body (save for a weighted blanket during savasana, and even that sometimes felt a little claustrophobic). In fact, I was afraid of it. When teachers guided us through “grounding” meditations or instructed us to feel the earth in an asana, I’d go right through earth to the other end of the spiral—ether—arriving in a happy, comfortable place of floaty suspension.

For those of us with more vata in our constitutions, this identification with movement itself might resonate more strongly. I once did an exercise with a therapist where he asked me to list off various words that described my sense of self (while moving, mind you—to encourage embodied rather than cognitive responses), and all the words I came up with were verbs. But the movement principle that is vata in the macrocosm is inherently related to all of our senses of Self. This is because of vata’s primary role in the organization and function of our organism, including the coordination between body, mind, and spirit. In the Ayurvedic texts, there is an entire chapter devoted to vata and its imbalances (pitta and kapha are included elsewhere); the stakes of our relationship with vata, with movement, couldn’t be higher:

Vayu is life, vayu is strength, vayu mainstays living organism, the same vayu is verily the universe, and hence the Lord Vayu is praised. [3]

When normal (non vitiated) vayu is at its abode with unobstructed (free) movement, [it] is responsible for long lifespan of hundred years devoid of diseases.

When these five [subdoshas of vata] are located in respective sites optimally, perform their functions, supports life without any morbidity.

—CS, Ci, 28/3, 4, 11

The teacher leading the online strength classes is/was a yogi, and so she was very aware of students like me who might be hesitant to switch gears so radically in their practices. “Strength is just a different kind of sensation,” she advised, pointing to the fact that there was no “good” or “bad” way to feel in one’s body (a very yogic/sattvic mindset, I might add). If we were used to feeling pulled-apart, stretchy, and limber from yoga, strength would literally feel different in our tissues—not just “harder,” but a whole different set of gunas. This wasn’t something to fear, but something to be curious about, to get to know over time like a new friend. Despite my near-constant low-grade pain, and knowing that adjusting my movement practices was key to other health goals I had at the time, I was still not so sure about these weights—these heavy things I’d have to pick up and put down over and over and then carry their resonance in my body even after I stopped. Did I really want to change the gunas I’d come to recognize as me? Would moving in a different way, feeling different qualities in my body, fundamentally change who I was? And what would consciously recognizing a need to build strength imply about my identity, my state of “normal”?

Moving into the heart of summer, strength might be on our minds for many reasons. The season of maximal body exposure, it’s a time when we all have to decide how much of ourselves to reveal to the sun’s rays for all the world to see—including ourselves. It’s a time when we have to really dive into what it means to be “comfortable in my skin,” since regardless of the size and cut of your clothing, the heat factor might make you not only expose more skin, but wish that you could crawl out of your skin all together. At the same time, as the culture of summer vacation invites a confounding expectation of elaborate and impressive displays of “relaxation,” we enter a mental tug-of-war between wanting—and needing—a break, a yin/tamas-immersion in hammocks and lakes as nature intended, and doing what we need to do to afford, even “earn,” such a break. In summer, we experience extremes of comfort and discomfort at the level of the body and the mind, often sacrificing one for the other, or both for the mere pursuit of an imagined ideal of summer.

In Ayurveda, it’s recommended that our diet, lifestyle, and routines support the qualities of the season to achieve harmony between us and our environment. That means that the sharp, hot, and transformative (yang) qualities of summer—aka pitta season—can be met with opposite qualities of softness, coolness, and stability (yin).

The way strength enters this equation is a bit of a riddle. In Ayurveda, and specifically in our year-long exploration of the srotmasi (channel system), we encounter strength in the tissue of muscle, mamsa dhatu, and its channel, the mamsavaha srotas—the focus of this month’s teachings. The karma, or action, of these structures falls more toward the yang side of the spectrum; with strength comes power, capability, movement itself, as well as the more masculine/yang cultural associations. But in their gunas—the qualities of the equipment used to build strength, the overall nature of the movement, the tissue generated by the activity and its overall effects on the body, we find something else. Compared to something like running, which is much more stimulating than the slow, steady, repetitive action of picking up heavy things and putting them down, strength indeed is more yin—grounding, nourishing, feminine. If you’re scratching your head at how these two things exist in the same place—how the practice that leaves you sweaty, panting, red in the face, and (sometimes) grunting is relaxing—you’re in the right train of thought. It’s a paradox, a conundrum. It’s life itself.

In the peak of summer, where our desire for fun meets our need for rest, where the intensity of the sun meets our surrender to coolness, where our strength is preserved for when it will be necessary in the dry, cold fall and winter ahead, we confront these opposing energies of yin and yang most directly. It’s right there in our faces—at the beach, on the subway, in our refrigerators. As we’ll explore here and this month in my classes, we’ll feel what it means to hold both aspects of strength at the same time—and through that discomfort and confusion, remember the wholeness of the Self that longs to move and be moved. No matter what your taste preferences for movement are, this summer we’ll all be building the capacity, resilience, softness, and spaciousness of the muscle at the core of all of our movements, yin and yang and everything in between: the heart-mind.

Muscle (mamsa dhatu) and its channel (mamsavaha srotas) are fairly straightforward in terms of their anatomy and physiology. (I say that with a wink-to-self, since I said that about last month’s theme and wound up writing more about it than any other srotas so far this year…) Most of us have an intellectual and visceral understanding of where muscle is and what it does in the body, according to modern medicine and health (and common sense). Muscle falls into three general categories:

- Smooth muscles, such as the stomach and bronchioles (in the lungs), the movement of which is involuntary

- Skeletal muscles, such as the quadriceps (thighs) and biceps (upper arms), the movement of which is voluntary

- Cardiac muscles, a type of smooth muscle controlled by the autonomic nervous system, so involuntary

When we talk about strength, we usually refer to the skeletal muscles that “grow” in size and capacity when exposed to an external load or resistance. Practices like yoga and walking use body weight as the load, which is inherently limiting and can only produce so much change in terms of strength in a biomechanical sense (but remember, there other kinds of strength). These muscles behave in three ways:

- Concentric contraction, where the muscle engages and the fibers contract (like a bicep curl)

- Eccentric contraction, where the muscle engages and the fibers lengthen (like straightening/lowering your arm after a bicep curl, controlling the movement down)

- Isometric contraction, where the muscle engages but neither lengthens nor contracts (like holding a bag of groceries in your hands; a “static” contraction)

A variety of loads, types of contractions, and movements are needed to create dynamic and responsive muscles. As one study posits, “heavy load training optimizes increases maximal strength, moderate load training optimizes increases muscle hypertrophy, and low-load training optimizes increases local muscular endurance. […] Based on the emerging evidence, we propose a new paradigm whereby muscular adaptations can be obtained, and in some cases optimized, across a wide spectrum of loading zones.”

The Ayurvedic classifications describe mamsa dhatu and mamsavaha srotas in slightly different terms:

Srotas

- Function—Plastering (lepana), movement, protection, strength, form, support

- Mula (root)—(snāyu) small tendons and fascia/ ligaments skin, rakta carrying vessels; six layers of the skin, mesoderm

- Marga (channel)—Entire muscle system, including smooth and involuntary

- Mukha (exit)—Pores of skin

Dhatu

- Upadhatu (byproduct): tvacha (skin) and vasā (subcutaneous fat)

- Mala (waste products): khamala (waste products of the spaces in the body–ear wax, nasal crust, sebaceous secretions, teeth plaque, smegma (reproductive secretions)

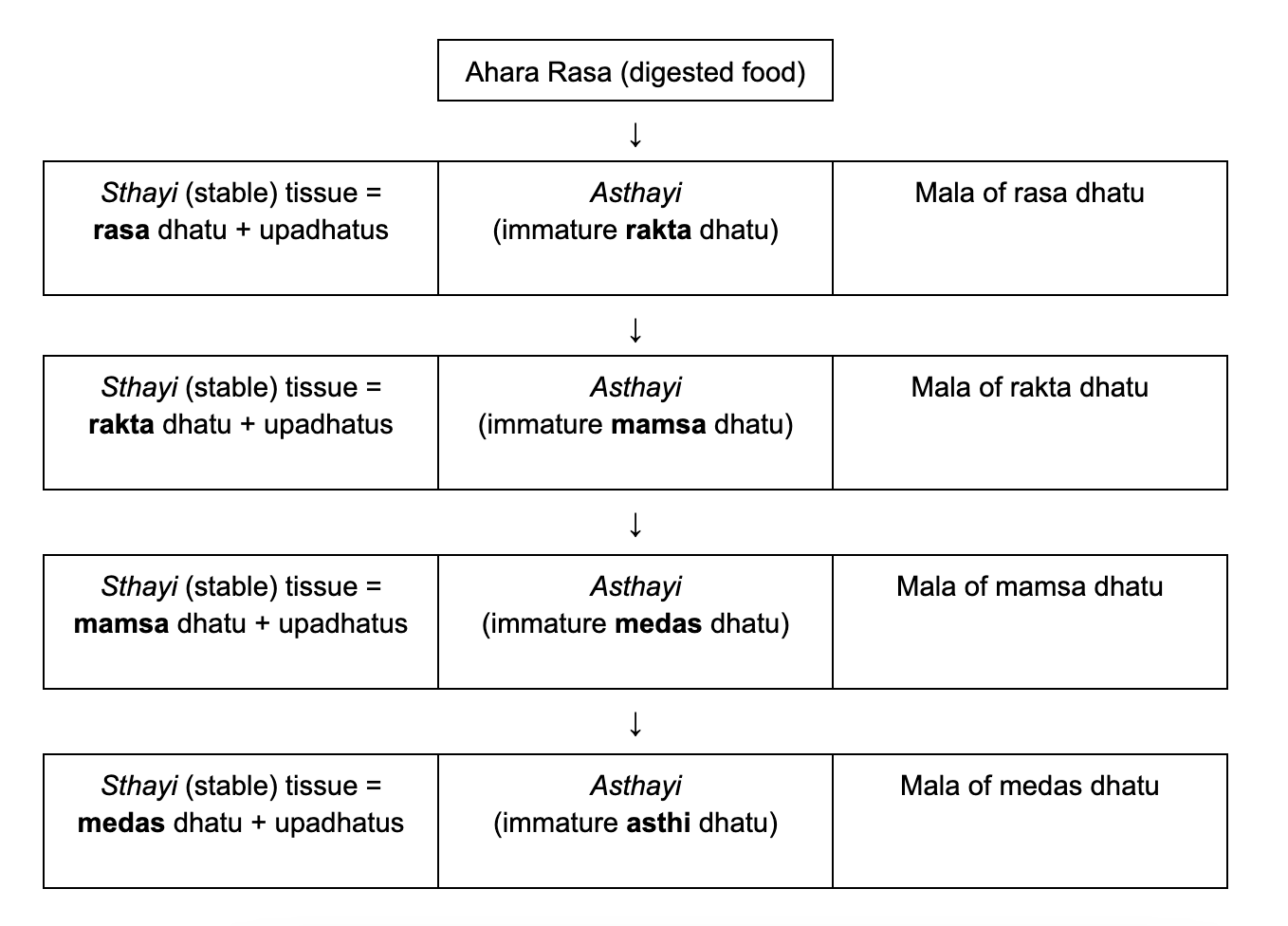

A few things stand out from these distinctions. First is the function: lepana, or plastering. In a most superficial way, muscles are what wrap around our bones, joints, and nerves, literally protecting these vital and more delicate aspects of our anatomy. Mamsa is the first truly “dense” tissue formed from the digestive process, after rasa (lymph) and rakta (blood), which brings us into new territory in terms of how this dhatu and srotas contributes to our health and sense of Self. While those first two more fluid layers provide general, you might even say more “universal” nutrition to the whole system, muscle offers form to our individual body that’s visibly unique. We can receive “fluids” or even a blood transfusion fairly easily, or donate those tissues and replenish them through our own digestive process, but it’s harder to donate or receive muscle—and all of the other tissues that come after. Mamsa stands at the juncture between what is ours and what is mine; what it circulating and what is stable; what is yang and what is yin.

While the major qualities of our body (height, stature, etc) are determined by our skeleton (a deeper dhatu that we’ll get to in a few months, and which suggests that the Self itself has layers), the muscles that cover that skeleton convey the “tone” of our identity. From muscle (and how much of it a person shows off), we can tell (though not with complete accuracy) what a person might be into, how they spend their time, how much they value their physical appearance. This includes not only our arms and legs and abs, but the small muscles of our face that indicate expression and emotion. The way one person cocks their head when their really listening; the way another person smirks on the left side of their mouth; the way an eye will twitch uncontrollably when someone is stressed or not able to speak their minds. These “movements”—gross and subtle—are how we know and express our Selves; they’re how we move and are moved by others.

The plastering of muscle forms a boundary around our bodies that at once shapes our identity and binds us in relationship to our environment. Not only by how we’re seen, but by how much resistance we invite into our lives by lifting heavy things—dumbbells and emotional baggage alike. Even without squats and lunges, our defining posture as humans—upright, walking on two legs—is the result of our relationship the most important and ubiquitous “external load” of all: gravity. Having to resist gravity has determined the shape of our spines, our pelvises, our feet, even our brains. Muscle protects us from the invisible, crushing weight of the air around us—even as the crushing weight of needing each other builds a kind of strength you can’t measure in reps and progressive overload.

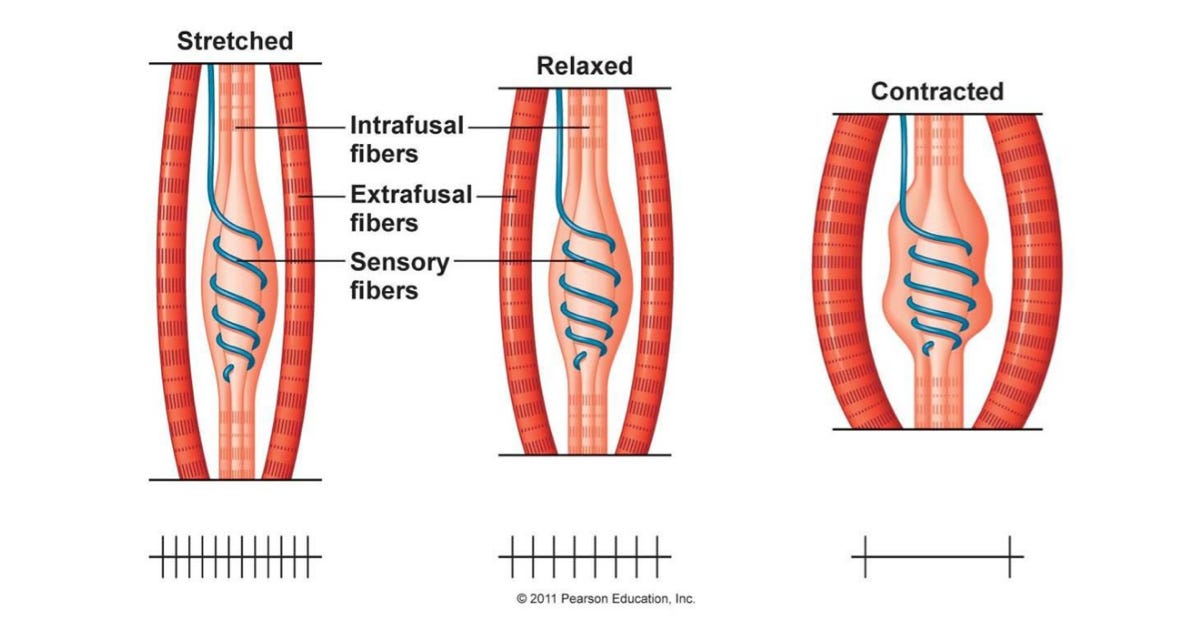

Lepana is also happening on a much more basic level in terms of muscles’ function. While most of us think about voluntary muscle-building through exercise, muscles’ job is to keep us alive. We can fight, flee, or freeze only because of muscles’ ability to contract and relax in response to signals from the nervous system; this includes the kind of subtle movement we might see expressed in emotion, but also the muscles that cause goosebumps or make our arm hair stand on end when we’re scared. They’re literal protection from death.

Muscles derive this live-saving power from their predecessor, blood (rakta dhatu), putting them in an intimate relationship with this coursing, fiery liquid whose job is vitality, or jivana. As such, Dr. Vasant Lad describes muscle as consisting of 10 percent fire (from rakta) and 90 percent earth (the muscle tissue itself, which is dense and heavy). Last month, I waxed poetic (or scientific?) about the nervous system and stress response, so you can review that material if you like here. Fed by blood, muscle invites us to examine the same question I posed last month: how much of our jivana is oriented toward surviving versus living. With rakta, surviving expresses as thickened, super-charged blood forced through a constricted vessel, whereas living expresses as “free and easy wandering”—the mind (and emotions, governed by the energetic liver) in its natural state of Sattva, or contentment, which also contributes to homeostasis in the physical body.

With mamsa, the expression is similarly contracted and tense in survival-mode. Ironically (or not?), this is the same state we actively assume when we lift heavy things on purpose (for fun or exercise). So what does muscle look like in Sattva, in homeostasis, in long-term health and healing—in yin? What does “plastering” look like when it’s not serving to separate the self from the danger of the Other?

The answer lies in the other interesting (to me, at least) part of the mamsa anatomy: its malas (waste products), which are a variety of pretty gross (pun intended) secretions from parts of the body we normally prefer to ignore or cover up. For some time, I struggled to make sense of their connection to muscle. They seemed more like the stuff of medas (adipose tissue—next month’s theme) given their oily, clogging, and generally undesirable nature. I mean, who really wants to think about their ear wax and, one of the top 10 Samskritam words out there, smegma?

But these malas bring us back to the relationship between stress and relaxation as expressed in a healthy state of digestion (agni)—particularly the dhatvagnis. These little fires that live in the kha (spaces) between tissue layers discern the quality and quantity of nutrition that each layer needs. As rakta becomes mamsa, we see byproducts (upadhatus) that offer even softer layers of protection above and below mamsa itself; and waste products that relate to our energy expenditure via our sense organs.

In the case of mamsa, this interstitial space also includes the fascia and tendons that hold the entire musculoskeletal structure together—an internal relationship and a space that allows for digestion of movement and information. As external load is transmitted between muscles, connective tissue, and bone, and vice versa, this communication pathway is not dissimilar to the way the feeling mind receives information from the sense organs and transmits it to the thinking mind, where higher level cognition and decision-making takes place. We don’t usually think of the brain as a muscle, but the mind is—an organ that moves between stimulation and relaxation, contraction and expansion, a constant spiral of activity that even resembles the spirals of muscle fibers and fascial lines that animate the mamaavaha srotas.

Digestion, remember, is the antithesis of the stress response, meaning that our typical strength-building activities—whether yang-style exercise or the expression of survival instincts—are what turn off or inhibit full and complete digestion. Incomplete digestion, in a more global way (through the main digestive fire, jatharagni) or at the dhatu level, will result in more of the dhatu and the mala, just at a sub-par quality. Consider this example from cooking: when you’re making rice, you start with a certain quantity of dry rice and water. If you cook it only halfway, you’ll get a pot of soupy, undercooked grains that’s more in quantity compared to the fluffy, fully integrated rice + water that, when compacted, might actually be less in quantity than the original rice + water. This happens when all of the dhatus are cooked, but especially with mamsa and medas.

When it comes to the muscle-building diet and digestive process, we can’t ignore the topic of protein. While this dense, building-block macro is necessary to support healthy muscle (protein doesn’t provide energy like carbs and fats, but rather provides structure), if digestion is compromised due to stress then those proteins will very easily clog the system. They won’t be diverted into storage like fats and carbs, so they become ama (metabolic waste) pretty immediately. The body’s main eliminatory system for protein is urine, so excess in undigested protein can cause dehydration and put strain the kidneys and create stones. (If you’re eating fatty proteins, like red meat, then the liver and gall bladder also get involved and potentially overworked.) In Eastern traditions, the kidneys are organs of the stress response—related to fear, the adrenals and their hormones—as well as the fonts of our vital essence, known as jing. Deficient jing compromises our immunity and overall energetic resilience. External strength, when not performed or attained with an attitude of yin, might drastically compromise the long-term strength of our whole system.

Undercooked muscle—that is, muscle built under stress without proper nutrition—can express itself in various ways. On the one hand, we might see someone who is very buff and fit—the typical gym rat. Their bodies are super-toned protein machines. But a muscle that is only ever allowed to contract—I.e., never comes out of the stress response—is not a functioning muscle from the perspective of lepana. The body lacks the proper perspective to be in relationship with its environment; unable to relax, it needs more and more fuel to maintain its defensive form of “strength.” In a real human context, these individuals might suffer in their relationships, too. So demanding and regimented are their workouts and diets, they cannot act spontaneously or accommodate other people’s preferences. The very thing—an “appealing” physique, and an energy of stability and groundednesss—that muscle presents itself to be actually turns out to be a “protective” covering for the opposite state of body and mind—an insecurity and desperate need to be in control. Relationship with self, others, and world is deeply distorted.

Muscles that derive strength from this kind of engagement—purely protective, reactive, resistant—are actually in a state of ksaya, or depletion. Their undercooked bulk (or lack thereof) is a reflection of the quality of the life force—the prana and rakta, supplying jivana—fueling and animating that tissue. Not trusting the outside world to be a place where safety is possible, even side-by-side with potential danger, there is undue pressure on the self to be in total control and vigilance at all times. This unresolved emotional tension manifests as myofascial tension—not only in the big muscles of the arms/legs/core, but in the face (think: furrowed brow, frown lines), and wrinkled skin. Maintaining a full-body grimace is hard work, and all of that effort drains the body of its juices (rasa and rakta), speeding up the aging process! As Dr Lad describes, “A person with weak mamsa dhatu feels like he carries the burden of the world on his shoulders” (129). And bearing that weight 24/7 is a recipe for further weakness, physiologically and spiritually. Under constant load and engagement, the muscle gives way. And when real danger comes along, the body won’t be able to protect itself through reactive movement or the physical barrier of the tissue itself.

In a clinical Ayurvedic context, the signs and symptoms of imbalance in mamas dhatu appear in the neck—a space where there’s a lot of movement, gross and subtle alike. Not only might the neck be abnormally large, but goiters and other growths (including thyroid tumors and tonsillitis) appear in the neck, indicative of imbalances in the body’s circadian rhythms and immune response. Our systems of defense have been hijacked and overused, and the channels create a protective barrier against more use that would bring the body to failure. We also see issues farther down the chain of dhatu nourishment, specifically with bone. Without getting too deep into the weeds of chemistry, muscle can more or less “steal” energy (vitamins, minerals) from the bone when it is prioritized due to stress or excessive working out. The blood becomes acidic when flooded with stress hormones, which leeches calcium from the bones. Fat offers a protective buffer against this theft; but when women especially go through menopause, the lack of estrogen reduces the bones’ protection, which leads us to question if strength is really happening when we tell menopausal women to lift weights without adequate nutrition or lifestyle guidelines to support overall homeostasis.

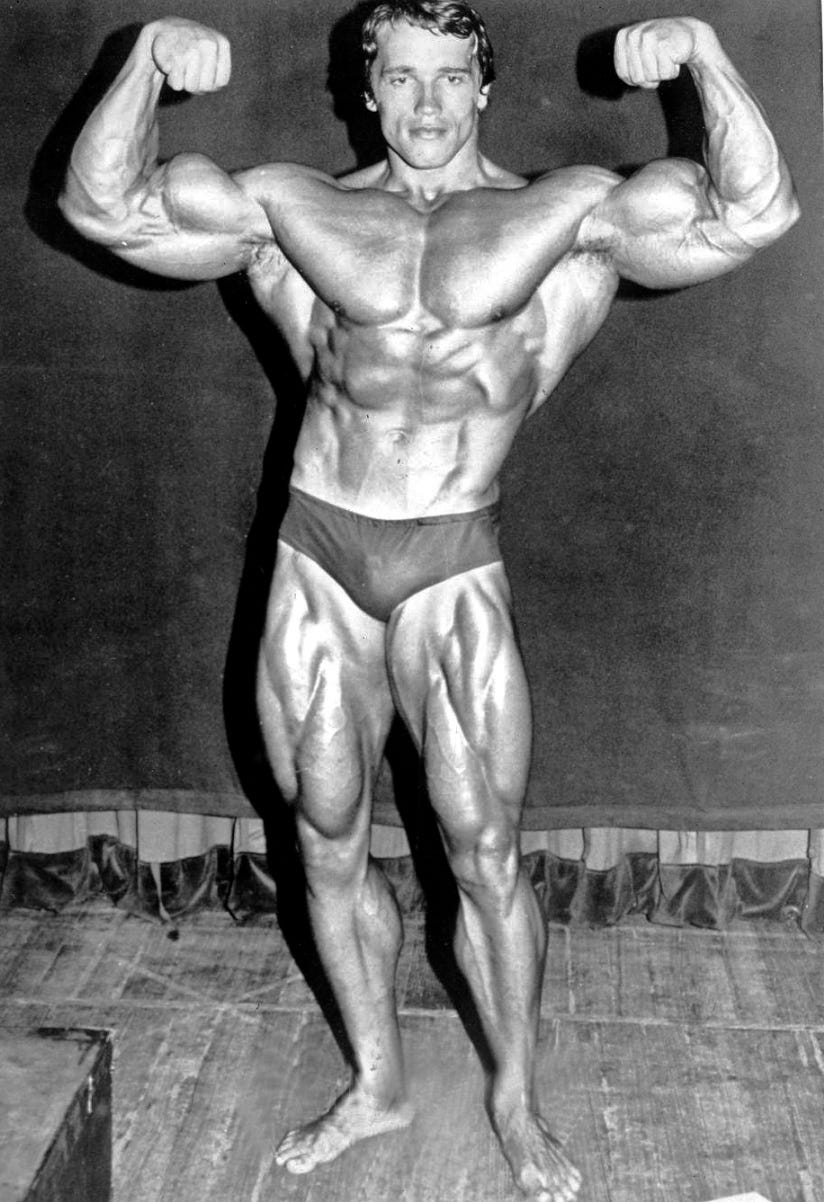

Now that we know what false/incomplete strength looks like, let’s reorient toward a healthier state of mamsa. Is there any better example than the best known body builder of our time, Arnold Schwarzenegger?

Now, most of us won’t ever look like this—and maybe you don’t even want to (I sure don’t). Maintaining a body like this is a full time job, as was the case for Arnold pre-silly family movies and political career. But we can see some things in this photo that illustrate healthy, yin+yang mamsa. The Ayurvedic texts describe mamsa as imparting ambition, confidence, competition, confidence, courage, and determination to the Self—yep, that’s here. In other words, a state of being (body, mind, spirit) that feels unthreatened, that doesn’t need to engage from a need to protect itself, but flexes as a way to invite relationship.

When we look closely at Arnold’s body here, we also see a most interesting paradox that reveals the truth of a healthy muscle. Our language employs words like “hard,” “sculpted,” and “ripped” to describe someone who is strong, but muscle—whether engaged or relaxed—is inherently soft. Do you see any straight lines or point edges on Arnold? Even while actively flexing, he’s all curves.

Let’s go ahead and feel this on ourselves, using a fairly neutral muscle: the calf. Prop up your foot on a chair so that your leg can be totally relaxed. Now touch it with your hand. It’s floppy, it jiggles, it hangs off the bone like a water balloon. Most other muscles will do that too when relaxed; you can try your quads in a legs-up-the-wall position, or even sitting with your legs out in front of you. In this state, the palpable feeling of muscle isn’t much different from fat—it’s only slightly denser, and of course made of different molecules. Yet our attitudes toward these two tissues that in their own ways offer protection to the body and mind couldn’t be more opposing. Why?

I have a few theories. In a superficial sense, muscle is inherently more yang—active, masculine—whereas fat is more yin—receptive, feminine. The patriarchal nature of most modern society puts a preference on all things yang; perhaps an underlying cause in the long-term taboos against women being or looking strong, and the relatively recent uptick in interest in strength training among women. In an attempt to (rightly) assert ourselves as valuable members of society, women are striving to attain, to BE, more yang.

Second, strength training often takes a very anatomical, precise, dissected view of the body that contrasts the more holistic way that fat—and, in reality, our whole universe—works. There’s the classic arm day/leg day approach, where you do specific exercises to target specific muscle groups. Although many movements are more compound that we give them credit for (squatting while holding weights works the legs most, but also the core and arms), the part-specific method of strength training actually works. If you do lunges every day, your legs will get bigger and stronger.

By contrast, targeted gaining or loss of fat is less under our control—no matter what the internet says. No diet or specific exercise will add or reduce fat deposits in one part of the body versus another. This defiance of our logical, anatomically-oriented mind is infuriating and frustrating, and we hate medas dhatu itself for not bending to our iron will. The only way to experience fat loss, or redistribution, is to deplete the body systemically. In Ayurveda, this is known as langhana (or “lightening”) therapy—which has a time and place, including to enhance one’s digestive fire if it’s been overburdened with hard-to-digest foods or emotions, or simply extinguished through stress. It’s important to realize that if someone’s agni is already depleted, then langhana takes a specific form. (Hint: it isn’t calorie restriction and intense workouts.) When the body senses it can’t digest well, it may hold onto fat as the easiest form of protection available, since building mamsa for plastering is more metabolically taxing (ahem, protein). Sensing a lack of safety and resources, the gut-mind wisely orients toward preservation than self-transformation and reduction. Once it lands in a place of harmony and homeostasis, then the nature of the tissues can take on a different tone. Langhana in this case looks like simplification of inputs, not reduction.

A more holistic and sustainable approach to strength is more like medas than we think—or would like to believe—oriented toward balance and internal cooperation, rather than isolation and growth. As Dr. Lad writes, “muscles have unity consciousness”—transmitting information and energy along lines of structure that allow for the smooth, yet multifaceted, movements that we often ignore like walking, sitting down, or reaching for something on a shelf (125). The conscious mind does not have to individually contract each muscle required for such movements; they fire together, in sequence, to move the whole body as needed.

In practice, this strength, where the load comes from internal coordination rather than external weights, looks more like yoga than a fitness trainer’s program—a mindset that challenges our desire to manipulate, control, and quantify our bodies and relationships. When we treat the mamsavaha srotas as an interconnected system, we must release our belief that plastering and protection—lepana—is something we do alone. Humans indeed evolved in groups—vigilance against nighttime predators lurking in the tall grasses was shared among tribe members; skills and resources were assigned based on interest and need rather than a desire to advance individual prestige or reputation. Each person played their role—just like the quads extend the knee, and the hamstrings flex the knee—but their efforts were oriented toward the health of the whole system, not to create “bulk” or “strength” in one area alone.

Building this kind of strength looks much different from what we’re being sold. Like Arnold when you look closely, it’s soft. Specifically, it’s supple. A strong muscle knows how to move between states of engagement and relaxation; it knows that if it’s always on, if it’s trying to carry the whole body (or, if it thinks it can/should shoulder that burden), it will wear out and put the whole system at risk. It gracefully and gratefully shares responsibility with its neighbors, even its antagonists (a technical term in physiology, meaning muscles that do opposing actions). Often in movement, we’ll see that a person is “dominant” in one area of the body as a compensation mechanism for weakness or lack of neurological connection with the partner or antagonist muscles. Rather than seeing this as a “problem” with one muscle—the stronger one, or the weaker one—we might see it as a form of intelligence expressing itself. The body needs to get a job done, and it’s using what’s available to do so. Rehabbing from an injury or imbalanced movement pattern of this nature isn’t about punishment for either offending muscle; it’s about establishing a healthy, cohesive relationship among the whole system.

As a yoga and Pilates teacher, I see this kind of thing all the time—really “strong” people who lack flexibility and mobility. There’s an idea that these two qualities are diametrically opposed and can’t live in the same body; I myself thought for a long time that I feel into the opposite extreme, really flexible but lacking strength. In reality, a strong muscle is one that feels safe opening up into a stretch (or simply non-contraction) because the whole channel knows it is integrated—plastered together. One of my favorite tricks to teach in class is doing some “strength” move—like a hamstring curl or glute activation—and then bringing students into a pose that lengthens that muscle. Without fail, there is more flexibility in a muscle that’s been working. The yang and yin abide simultaneously to create ease in all movement.

Fitness culture of all disciplines puts undue burden on our individual will and activities to keep the body healthy. Unless we are proactively exercising, we can’t expect to be “strong,” they say. While it’s true that in our mostly-sendentary culture, we need to put more deliberate effort into movement than a century or more ago, working out isn’t the only way to maintain, or even grow, strength and mamsa dhatu. Continuing with the holistic lens, emphasizing relationship and diversity over isolation and specialization will make movement/exercise not only more effective, but more fun. As studies show, working out for an hour—or even three hours—a day won’t make up for spending the other twenty-plus hours of the day sitting or lying down (couch or sleeping); we need to integrate movement in small, regular intervals. Our muscles need a steady dose of interaction with gravity, in different planes of motion, otherwise they will fall into patterns of compensation, fatigue, and neurological disconnect.

Take this example: a person goes to the gym every morning, “crushing it” with cardio and lifting and even some yoga. But then they go to the office for a sitting marathon—they don’t even need to get up to get their super-healthy protein-veg lunch since it’s delivered to their desk, and they eat while staring at a screen. On the surface, this person is the picture of health, but on the inside the attachment to their routines, the movements of their life, is so rigid that if one falls away the whole system breaks. And if they’re not at their desk, earning money for their families, whatever ego-fueled beliefs or fears they’ve built up, the even bigger system of relationships falls apart. Another example might be an elderly person who wakes up, takes their dog on a walk, comes home and piddles around the house doing daily tasks, maybe meets a friend for lunch, maybe takes a nap, goes out to the garden, walks to the store to get fresh bread for dinner. Their body isn’t “ripped” or “cut,” but in terms of relationships, they might be “stronger” than person #1. The variety in their days makes each task less precious, reducing the need to hold on and “protect” it, and reducing their own self-importance to the system. Their strength allows them to soften into the flow of the day, the days flowing into seasons, the seasons flowing into years. This kind of strength is what builds a community from its members, rather than its members imposing a structure or vision upon the community.

Supple strength brings us back to the yin/yang duality that possesses us when it comes to our bodies and our roles in relationships. In this approach, we see these two opposites not as foes, but as friends—ying and yang containing, supporting, and creating each other. From a physiological perspective, it’s actually in the periods of rest (yin) where strength is built—it’s when the muscle fibers that were literally torn apart in exercise stitch back together, stronger for re-uniting. The same thing happens in our minds, where through rest, sleep, and meditation our neurology demonstrates its “plastic” nature—the brain is washed in cerebrospinal fluid every night, digesting and eliminating neurotoxins, even as things that we learned during our waking hours (movement, as well as information) integrate into our body of memory. Rest is when our body and mind “learns,” so that when we come back into our activities (yang) there is an established groove we can follow, exerting less mental and physical energy to do something we’ve already done. The more we practice something, the deeper the groove gets. We become “stronger,” better at an activity when we learn how to do it with less effort.

This practice is nothing more than a state of Yoga. As Dr. Lad describes, “muscles bring skill in action”—the definition of yoga given in the Bhagavad Gita, from Lord Krishna to the confused warrior Arjuna—”which is art. . . . Coordination involves groups of muscles working together harmoniously in order to bring skilful action” (123).

Culturally, the yin/yang duality appears through the gender roles that (amazingly, still) dominate our relationships and their conflicts. The idea that one person in a relationship, regardless of their biology or gender identity, is the “yang”—the active one, the “bread winner,” the provider—and the other is the “yin”—the passive one, the caretaker, the peacemaker—ultimately weakens the relationship on the whole. Stuck in their lane, each individual limits their potential for growth, the ways they can enhance and challenge the system. Over time, it’s easy for resentment and divergence to overcome the relationship since those rigid roles become more and more fixed. The recognize their need for the opposite qualities, but unable to generate or access them themselves, they go into protection-mode. Their movements aren’t coordinated, but inflexible and resistant.

Recognizing our need for each other in relationships is not a matter of being “completed” by someone else, as Tom Cruise planted in the Millennial mind. Rather, the strength of a relational muscle recognizes the complementary and adaptable nature of each of our individual skillsets, personalities, and interests. Even when “opposites attract,” in a healthy dynamic, it’s not because one is compensating for the other. It’s a recognition of the essentialness of every facet in the wholeness of the system—the tao that comprises both yin and yang, and a sacrifice of me for the health of us. This strength is both confident and non-attached, where one muscle (or person’s) inherent stability and trust in its neighbors creates a body that is strong. Such cohesion is what we’re striving for in a state of Yoga, defined by Patanjali as sthira sukham asanam—postures that possess effort and ease, not in alternation but simultaneously. The body can relax when it knows it is strong all over, just like we can fall into relationship and community—fall in love—when we trust that we are just as strong in ourselves as we are together. “To love someone without expectation is the greatest love,” Dr. Lad writes. “That will happen only when your action becomes motiveless–not less motive, but motiveless. That one action for a fraction of a second, without motive, will bring transformation” (132).

Like with most routines and practices, the way each of us engages with strength and mamsa dhatu will change over time. Injuries happen, age happens, busy schedules happen, life happens, and we fall in and out of our routines. Trusting that the body knows how to protect itself even without our conscious effort is one of the best skills and truths we can learn from a strength practice. As I’ve incorporated lifting heavy things into my movement diet, I’ve found that my teacher was right when she said that strength would provide me with a different sensation in my body—and mind. The felt sense of internal, global stability in my body has created a freedom and flexibility in my mind (and, actually, a little less flexibility in my body, which I needed to stop all those little injuries).

Before, my movement-identity was close to possession. I needed to move—to settle all the vata in my body and rajas in my mind, exhausting myself into a place of stability and tamas. If I didn’t move, I wasn’t okay, which fueled the need to move more. But the activities I was most drawn to weren’t providing the gunas I needed; they would often spurn the vata and rajas, perpetuating the cycle of yang and never allowing me to find strength or health. Now, the desperate need to move that defined my life before has quieted, and I choose to move, and what kind of movement, because I have a baseline of okay-ness that I want to maintain. I’m not attached to or dependent on a super rigid exercise schedule, because I know that I can come back to it when I need. I’ve become more fluent in the sensorial language of my body, making it easier to move in a way that meets the needs of the moment. When my hip flexors feel a little like old stockings that have dried out and flake apart in your hands, I know I need to do some deadlifts and isometric psoas work. When I feel a nervous emptiness in my chest, I know I need to do seated twists and spinal undulations. When I don’t know how I feel but I know something’s up, I start with an amuse bouche of joint rotations (dasha chalana), and literally allow that fluidity in the spaces between muscles and bones to carry me on to the next pose, exercise, or breath.

My initial fear of changing the gunas that defined my moving self wasn’t totally wrong. I’m still light, agile, and restless—and I can also be heavy, dense, and still. The strength I’ve built didn’t replace any part of me; it expanded my capacity to live and move through the full spectrum of gunas. It’s granted me access to not more of my-self, but to more of the Self that is beyond qualities and actions, that is Yoga.

Yoga has long been referred to as a “moving meditation,” and I believe that it’s possible to do all kinds of exercise with a meditative/mindful quality—i.e., focusing on the holistic, collaborative qualities of the movement, what my teacher calls “global body awareness,” rather than isolation and quantitative “growth.” But even in broader way, we can connect the state of ease in the nervous system, digestion, and all systems of health and healing that comes from true strength with a state of meditation that gives us more choices for how to live. In yoga and Ayurveda, we describe this state of mind as sattva, which means harmonious, clear, and steady. This mind is not turned “off,” as many people believe it should be in meditation (and avoid/quit the practice because they [rightly] believe their minds won’t ever turn off). A sattvic mind is like a body of water pulsing from the dynamic tension between movement and stillness—the flow of the deep current held in a steady rhythm as momentum. “The mind in meditation is a muscle in action with relaxation,” says Dr. Lad, a logic-puzzle that is solved not through thinking, not through isolating and parsing out individual words, but through experiencing it (131). A strong mind is one that plasters itself with sattva.

Could meditation be a strength-training practice? It might be the perfect one to take on during the summer season, when adding active/yang-style movement into your diet is just as contraindicated as a diet of kombucha and chili peppers. This month in my classes, we’ll be exploring the various facets of strength through my favorite three-prong approach: softening (rolling/myofascial release), strengthening (active engagement/work), and stretching (relaxation/restorative postures). Each week in July we’ll explore a different body system not for the sake of heightening its individual prowess, but for contributing to the felt sense of wholeness in our body-mind complex. How is leg day also arm day? Are backbends strengthening for the arms/chest, the legs/glutes, or the core? All together, the month will be a complete “workout,” geared toward reversing the spiral of effort and attention that can so easily be fragmented, especially this time of year as vacations, socializing, and all sorts of bright-shiny objects pull us away from routine and cohesiveness—away from our home, in the heart. Because of the emphasis on wholeness, any of the individual practices, or micro-practices they comprise, can be done on its own while still working the whole body. Ultimately, the practices will make us aware of how integrated we really are, even while one body part or muscle group takes center stage. Whether or not someone meditates already, this perspective of radical acceptance and integration strengthens the muscles of the feeling and thinking minds that are necessary for remembering the inherent nature of the mind in sattva. When we stop trying to meditate, meditation happens:

When people use meditation solely for stress release, they frequently have problems with it. As they try to be quiet, many thoughts and feelings come to consciousness and they become disturbed. When there is a purpose behind meditation, the value of medication is reduced. Purpose is expectation and expectation is desire. One should meditate with only the desire to meditate; that’s it. Do not have expectation. […] [Technique makes] the mind mechanical, and a mechanical mind is a narrow and limited mind. […] The ultimate flowering of meditation should be spontaneous. Every action then becomes meditation. Eating food, drinking water, working, driving a car, ironing a shirt, and even washing dishes can be meditation. Then the entire life is meditation and stress has no place. (131)

Setting an intention for your movement-identity as strong, consider the gunas you already have and which ones you might make more space for, which ones you haven’t had the practice of feeling yet. How will you know they’ve arrived? It’s ultimately up to you, but in my experience—as a teacher and life-long student of movement—being strong makes things easier. Lighter. Softer. I encourage you to remember the yin inside your yang, and the yang inside your yin, and notice what it feels like when they are plastered together in the unmoving, unchanging light of your spirit expressing itself through movement.