Enter the space inside your head.

See it as already infinite,

Extending forever in all directions.

This spaciousness that you are

Is permeated by luminosity.

Know this radiance

As the soul of the world.

—The Radiance Sutras, 62

“I spend so much time and energy taking care of others. So I’m here to recharge and fill my cup.” I hear these words, or some version of them, every time I attend or assist a yoga retreat. I’ve uttered them myself in opening circles . . . and in therapy and body work sessions. Watching your tank arrive at EMPTY, and even cruise as long as you can past empty, is a familiar, if not expected, part of our personal and professional trajectories these days. Just the way that “busy” became a humble-brag, then near-meaningless, answer to “how are you?” in recent years, “filling our cups” has been usurped by the Wellness Industrial Complex as a thing we need to do semi-regularly with elaborate, expensive, and/or extreme pauses from our day-to-day life where we indulge in “self-care” (mostly, eating and sleeping and spending time in nature, activities that, for the vast part of human history, were precisely the stuff of day-to-day life).

I’m not undermining the value of retreats—they’re part of my self-care practices and, like other holidays and traditions, help to punctuate time with both a refreshing change of pace and a realistic reminder of change. For the past several years, I’ve been attending an annual retreat with my yoga teacher and more or less the same group of students every fall. Nearly everything—the location, the people, the food, even the bedding—is the same every time I return, but I am always so different. I remember arriving there in 2021 (I skipped 2020, though a small group did valiantly attend and wore masks for all five days), and feeling the difference at the level of my organs. For the first day, I couldn’t get over the fact that my dad was alive the last time I was there; and this time, he wasn’t alive anymore. I’d never be in that place, in that studio, in that dining room, the same way again—with a whole, in tact family; with a whole, in tact heart. Of course, none of us can ever return to the same place in the same way, but this was a significant shift that changed the way I practiced that year, and ever since. As painful and startling as it was, having a steady backdrop against which to see the contrast of my own evolution was a deep experience of yoga—much deeper than the scorpion pose backbends and posture labs we did on the mat.

In the wake of such major life events—illness, deaths, losses of jobs and partners and pets and children flown from the nest—retreating for the purpose of refilling the cup that has been quite literally emptied makes total sense. Such pauses are often essential to the long-term healing process that continues after the week or weekend of not having to do laundry, enjoying meals cooked by someone else, and having people cover you in blankets, prop your head with cushions, and lull you into deep relaxation with soothing music.

Listening to some students’ cup-filling intentions at a recent retreat, I was so glad that they’d heard and responded to the whisper to care for themselves that can so easily be drowned out by the roar of grief. My reaction to others’ shares, though, surprised me: I was sad. Sad to hear that they’d waited weeks, months, years, decades to fill their cups. Sad that there were prescribed intervals of time and ways to execute this fundamental right to a body that isn’t exhausted, to a mind that is calm and clear, to a heart that feels its belonging. Sad to think they might fill themselves up, even if only part way, in the 48-ish hours we had together, and then immediately start emptying themselves again.

And then, I started thinking: what if we’ve got this whole cup metaphor backwards? Our bodies are not machines—cars that hold a certain amount of gasoline, electronics that hold a certain amount of charge, before they need to be re-juiced. In those real systems, the source of fuel is material and transformed into a different kind of energy while being used. Our systems are different. Our fuel, our energy, our power isn’t material. Not even the calories and macros we consume via food, which we “burn up” when we move and think and simply exist in a living body, are really giving us power. It’s something else, something that isn’t meant to be stored and used up progressively like liquid in a cup, vase, or the vessel of your choice. It’s prana.

As I’m writing, I’m driving through an idyllic corner of New England where the tips of the trees are just starting to turn golden and curl in on themselves. Nature’s cup is emptying; it’s easier to see, and feel, the spaces between things. Edges are more defined in the clear autumnal light; shadows fall earlier and longer, increasing our risk of falling into the dark abysses of our minds and emotions; there is more night than day, and our squirrel instincts to gather and hold wax in response to the inevitable scarcity of the season ahead.

The emptiness between these pronounced spaces—of tree branches, of our days, of our relationships—invites the energy of the vata dosha into our macro and microcosms. Made of space and air (aka, nothing), vata typically dominates the final phase of any life cycle—animal, vegetable, fungi, or otherwise. Its restless movement and dynamic creative power will lead the system toward disintegration and, ultimately, death. The qualities we see in nature in autumn—dry, light, rough, subtle—are harbingers of ending; hence the emphasis on warm, oily, and grounding substances in Ayurveda as forms of nourishment for our bodies as we try to keep them alive for as long as possible.

But these days, vata is so prominent in our inner and outer worlds that we don’t just see it in the latter decades of life, where responsibility and busyness aren’t expected and that vata can invite deeper introspection and communion with spirit. Dysregulated by vata in our thirties, twenties, and earlier, our cups are emptying before they ever really know what “full” feels like. We’re not as plagued by monkey-minds as we are by squirrel-minds—scampering around, eyeing every acorn like it’s our only hope for another day, and every fellow squirrel like they’re our worst enemy for posing a threat to the desperate satisfaction of our needs.

But because vata can flip from destructive to delightful on a dime—like those ombre October sunrises that dazzle our senses, and the trees that bleed out rivers of merlot and ochre—it’s easy to mistake our feeling of being run-down, burned-out, emptied with life itself. Confused by whether we’re high or low, we put off dealing with the situation until we can’t. We wait 12 months, or 12 years, for all the pieces to align perfectly and schedule our “retreat.” At that point, a weekend of yoga feels like a drop of water on an August lawn. It’s a relief from being absolutely parched, but hardly enough to quench our true thirst.

While we can have more or less prana in our system at any given time—more when we’re engaged in a dynamic activity, like running or yoga or sex; less when we’re emotionally disturbed or tired or hungry (think: a wilting houseplant)—no body can have “too much” or “too little” prana as a baseline. What affects our ability to derive the subtle nourishment of prana is how much space we make for it.

Prana needs to circulate—the system ebbing and flowing between empty and full—to do its job.

Our culture has made us believe we can stock up and replenish, or bottom out and crash, in extreme swings without damaging our system. It’s a qualitative, capitalist, vata-aggravating view of the world. Prana asks us to treat our lives—our cups and their contents—differently. We don’t try to eat all of our food for the week in one day; we don’t try to work out for 7 hours straight and lay on the couch the rest of the week; we can’t “catch up on sleep,” no matter how hard you try or who sells you a pill/tincture/crystal that promises to do that. We don’t only inhale. These vital life processes—the evidence and manifestations of prana—happen incrementally, regularly, but also dynamically. What we eat, how much we move, how much sleep we need, the pace and depth of our breathing changes not only season to season or day to day, but moment to moment.

What we need to make those micro adjustments and truly get our needs met, rather than following a formula or going into squirrel-mode, is the same as what prana needs for its circulation: space. In this case, it’s mental space, aka attention. The greater the pause between thoughts—worries, to-do lists, schedules, work assignments, retreat-planning—and the greater the pause between the activities driven by those thoughts, the more the manas, or feeling mind, can be sensed and satisfied. If in the space between hitting SEND on the reply to email #10,784 in your inbox and opening email #10,785, you paused and put your attention on your breath, you might notice that you’re a little thirsty, or a little cold, or maybe you have to poop. Or that you haven’t talked to your mom in a week. Or that your living, breathing, fleshy partner is a few feet away from you across the room, but you haven’t spoken in hours because you’re both So Busy. Simply putting your attention on any of those details, or any of the infinitely more details that could be true, will infuse that part of your reality with prana, regardless of how you act. Once prana-fied, it might long for more attention and bring you back into the material world. Once in the material world, you might feel like yourself again.

Prana follows attention, so the teaching goes, and so we know from firsthand experience. A few years ago when I was very sick, one of the more interesting symptoms I experienced was painful swelling in my foot and ankle. I could barely put weight on it let alone walk, but somehow I made it to almost all of my yoga classes (which was probably a mistake; I may be a yoga teacher, but I’m not immune to the cup-emptying compulsions of the world). Remarkably, I began to notice that the debilitating pain, which could bring me to tears just while sitting on the couch, was barely present while I was teaching. My attention, and my prana, had moved away from the pain, and so its power diminished (albeit temporarily).

This happens all the time: you’re ruminating over a work email and then suddenly get a call with bad news (or good news!), and work means nothing; you’re in an anxiety loop about some past conflict but get absorbed in a book or show and forget all about it. Distraction, when used wisely, is a powerful tool for healing. Taking our mind off things won’t make a real problem go away, but it can help give some helpful distance, some space, from the initial intensity of reaction to discern if this is a real problem anyway. Redirecting the flow of prana so that a fresh supply of energy can help us handle the situation more effectively, or simply let it go and enjoy the relief of an over-filled space being emptied.

Life doesn’t happen only when we’re full. It happens in the spaces in between. Our willingness to make that space, attend to it, and choose to fill it or let it be is what rejuvenates us.

Modern Ayurveda is often taught along the lines of the empty-full cup metaphor. Too much vata? “Balance” it with some ojas milk and abhyanga. Too much kapha? Take a brisk walk and eat mustard seeds. The linear, either/or, “opposites-balance” interpretation of Ayurveda directs our attention, and our prana, to places of deficiency, which of course feeds that model of selfhood as something that always needs fixing. It also suggests there is some ideal ratio of doshas, elements, gunas, or dhatus that we are seeking to attain and then hold onto for as long as we can. In reality, each of us is made from a unique combination of all of those ingredients that will need different sources of prana to maintain over the course of our lives.

Healing isn’t about finding the right inputs and filling up on those, but rather about of observing whether our current state is allowing for enough circulation of prana.

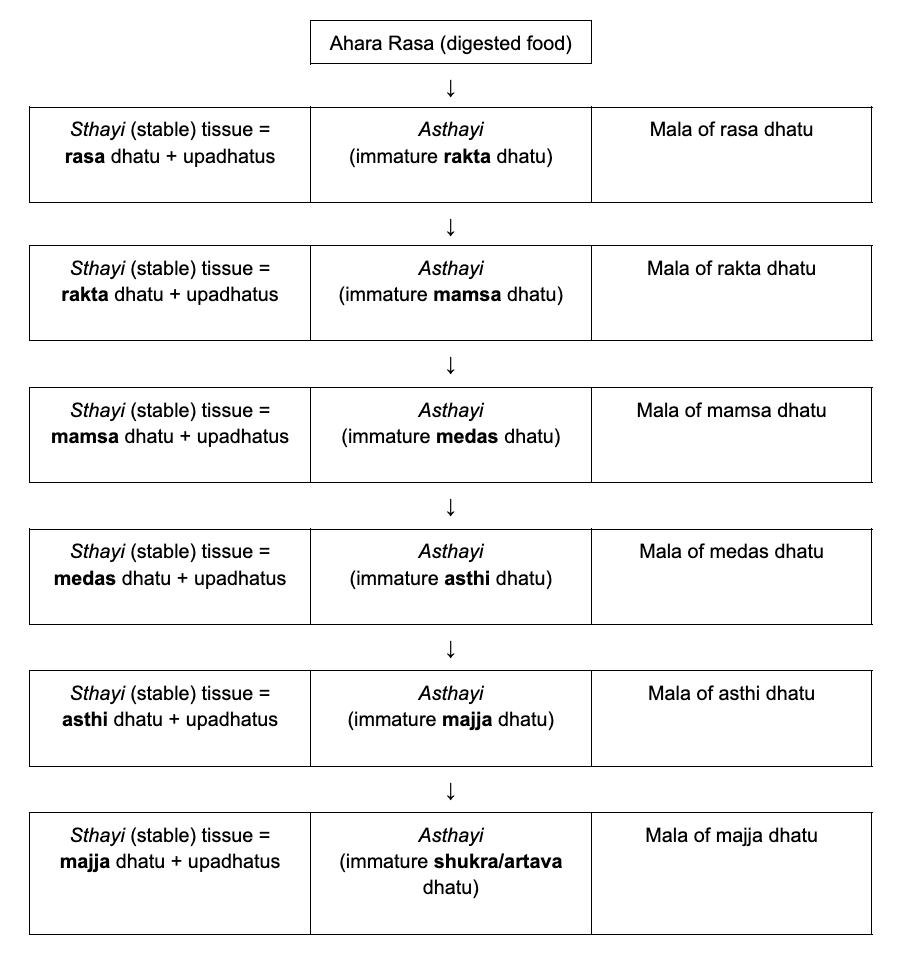

The good news is that prana is everywhere, which means our options for healing are abundant. But we can experience its subtle, dynamic, stabilizing-but-not-filling nature through one of our deepest core dhatus and srotamsi, majja, which is my theme for this month.

Majja Dhatu

- Function: Fills spaces, nervous response to stimulation/pūrnima

- Mala: Fatty material of the eyes, skin, and feces (snigdhatā of akṣi, tvacā purīṣa)

- Upadhatu: None (debatable)

- Quantity: 1 añjali (½ the amount of fat in the whole body; ¼ the amount of blood)

Majja can be understood as several different bodily substances: namely, bone marrow and nerve tissue. But when we look at the function of majja—pūrnima, or “filling”— we see that it’s much more pervasive. Marrow and nerves literally fill the spaces in bones and the spinal cord, respectively, but majja includes anything encased in bone: synovial fluid of joints, the brain and cerebrospinal fluid, and the eyes. These different forms of majja not too dissimilar in their broader physiological functions, either. All of these substances act as conduits of information; they exist because of a fundamental movement happening in the tissues around them. From a guna perspective, these substances look a lot like kapha: oily, dense, viscous, fluid. But their function is much more like vata—or, given that the nature of this movement is so refined and subtle, more like prana. The movement that happens in majja isn’t like the gross movements of the more superficial dhatus: lymph and blood and muscle and even bone. It’s the will, the direction, to move inside the movement—literally. It’s the beat inside the melody. It’s prana filling the space of life with life.

A teacher recently clarified an important aspect of Ayurvedic anatomy that breaks down, in an exciting way, the neat categories we have for body parts, organ systems, and all the other components of our sharira (physical body; “that which decays”). He said that anything in the body that contributes to the function stated in the texts is part of that dhatu and strotas. In the case of pūrnima (and this is a bit of extrapolation/interpretation from me, so bear with me), I would apply this concept to bring prana itself into the realm of majja. Let me explain my thinking by way of the majjavaha srotas, or channel of majja.

Majjavaha Srotas

- Mula: Brain, spinal cord, asthi sandhi (bone joints), joints and junctions between dhātus

- Marga: Entire nervous system

- Mukha: Synaptic space

I started this year with the intention of teaching how all of the srotamsi ultimately lead to and affect the channel of the mind, and I believe I’ve been mostly successful in doing so. But my case isn’t that hard to make with majja, since it’s more or less synonymous with the mind—or, at least, the nervous system that transmits the directions and information received and created by the mind. The mind itself has an aspect of pūrnima in its expression: our biggest shared complaint is that our minds are so full with things we wish weren’t occupying our attention. This is the kind of distraction most of us associate that word with (not the healthy, space-making kind). A full mind makes us feel drained, and (ironically) seek cup-filling activities like yoga retreats as an antidote to this mental state. We are desperate to “get out of our heads,” to “turn off our thoughts,” to “empty our minds.”

But our brains, our nervous systems, and our minds are designed to be information-receptors; they’re really more like sense organs than the command center that Pixar and the like have made us believe. We only really register a very small amount of the information these systems receive all day every day; if you thought you were overwhelmed now, imagine having X% more sensory information to digest. When we encounter a full mind, unfortunately there’s no real way to empty it of its content; if the mind wasn’t occupied working 24/7, we’d be in trouble.

The answer is, again, in space—and the attention that can fill that space, and the prana that follows. Directing attention away from thoughts, and activities that fuel the troublesome thoughts, simply gives us a bigger container in which they can dwell and move. Their difficulties become less concentrated in a wider field of awareness; we might be feeling the pain of a loved one who is sick, and we can laugh out loud at a friend’s joke without either emotion erasing the other.

Going one step further, our attention is not limited by material reality, which is why the yogis are always talking about turning attention inward (pratyahara, or redirection of the senses) as a tool for calming the mind. The inner landscape cannot be described in the same terms as what’s outside, with shapes and colors and forms. But we can experience a kind of fullness and satisfaction in exploring that beyond-mind space. Society does everything it can to keep us away from that space, because then we wouldn’t need to buy anything to correct all of our infinite flaws and inadequacies.

Filling the space of you with your attention, you know you are already full.

Imbalances in majja express in all the ways you’d expect related to the nervous system: anxiety, restlessness, difficulty focusing, uneven mood/energy, conditions like Parkinson’s and dementia where cognition declines due to nervous tissue degeneration. The connection to the senses also invites a particular set of symptoms related to the eyes. Dry, red, burning, twitching eyes, when accompanied by anxiety, are a sure sign of majja ksaya (deficiency)—literal burn out of the sense that we most closely identify with as humans. Unable to perceive our external world, there’s little chance these tired eyes can navigate our internal world.

Blind to our own inherent fullness, we seek the fastest, cheapest substitutes for prana to pour into our cups.

The connection to the eyes invites several interesting practices that I’ll explore throughout the month in class. Of course there’s the underappreciated eye yoga—stretches for the eyes themselves that help to reset vision and bring fresh nutrients to the eyes, as well as relieve tension from the back of the head (occiput) that can create headaches, jaw tension, and neck and shoulder pain. Energetically, the eyes are a crossroads of several different organ meridians (per TCM) that relate to the flow of energy and emotions a la prana/qi.

- (yang) Small intestine – outer and inner corner

- (yin) Heart – lower middle

- (yang) Bladder – inner corner and up

- (yang) Gall bladder – temple

- (yin) Liver – passes through the center of the eye

Restoring our capacity for inner sight is the antidote to the external darkness that’s increasing around us. It’s said in Ayurveda that the dhatu kalas—the space between tissues—are where the agni of that dhatus live: the fire that transforms and passes nutrients from one layer to the next. Fire also shows up in majja-related imbalances in these Chinese organs, especially the liver and heart. A pattern of disharmony known as “liver fire rising” will manifest in red, irritated, unstable eyes, as well as intense and violent dreams (think: a wild fire of the inner eye, incinerating our sleep-prana); a peeled, red tongue tip, indicating heart yin deficiency, is common across the board these days due to pervasive stress, but especially with liver fire rising. Essentially, in this pattern the liver yin, which grounds the heart-mind and ensures a smooth flow of emotions, has been dried up, and so the relatively excess yang “rises” (like all heat does) into the head and eyes; that fire also contributes to heat in the heart, which is fed by the liver. (In Ayurveda, all of this falls into the realm of pitta, especially imbalances in sadhaka pitta, which lives in the heart and brain governing intellect and emotional wisdom.)

There are so many ways to work with such imbalances, but one simple and very effective remedy is ghee. Consuming this super-refined fat—quite similar to majja, actually—we not only improve the quality of our jatharagni (main digestive fire), but all of the micro-agnis throughout the body down to the cellular and microbiome level. This is the sight that tells us if we’re truly full or empty, if we’re truly satisfied. Ghee ensures digestion of all that we take in as food or sensory stimuli, such that the whole system can derive stability from prana.

But beyond ghee, nutrition for majja couldn’t be more important. Since it is such a deep dhatu, agni needs to be strong to ensure prana gets through the previous five dhatus with enough left for majja and the last dhatu plus ojas that follow it. The regulation of prana in the form of emotions/stress, governed largely by the liver and heart per TCM, is a baseline for ensuring that agni is not distracted, overwhelmed, or burned out, thereby preventing proper digestion. Hence why pranayama practice will be a key aspect of this month’s work. Last month, we used mantra as a way to hook the thinking mind to the breath via sound with meaning, articulation, and rhythm. Now, we are strong enough to release the hook and float out into the sea of breath.

“Every breath is a sacrament, an affirmation of our connection with all other living things, a renewal of our link with our ancestors and a contribution to generations yet to come. Our breath is a part of life’s breath, the ocean of air that envelopes the earth.” —David Suzuki

But we also need to look at the agni and satiety of the immediately surrounding dhatus that might interfere with majja’s share of the pie—or, from which majja might sneak bites off their plates when no one is looking. When we talked about asthi (bone,) I explained that mamsa (muscle) can steal energy from bone because of its high-energy requirements: if muscle can’t activate when we need to fight, flee, or freeze to protect the whole system, then strong bone isn’t of much use. But between mamsa and asthi is medas (fat), which acts as the nutritive buffer and parent of majja. With medas around bone, and majja inside bone, bone is totally satisfied. But majja, too, can be a hungry dhatu—after all, its conducting information to the whole system 24/7, from hormone regulation to kinetic movement, from unconscious autonomic reactions (like jumping out of the way of an oncoming car) to the coordination of conscious movement (like dance or yoga or running). What majja wants—if the mind is overactive or the nervous system is overfiring due to stress—majja gets, bypassing medas and asthi and/or not leaving enough for reproductive tissue that comes next. Essentially, we need enough medas to supply medas, asthi, and majja with nourishment.

So, ghee. And, all foods. Any food, really. Because while certain foods will support these dhatus more directly because of their makeup, any food that’s digested is going to contribute to the nourishment of the system. Because at the core of any food is prana.

What you need to complete that task will totally depend on what your majja is filling and the kind of movement it’s orchestrating. Are you picking up heavy things and putting them down three to four times a week? Are you growing or nursing a baby? Are you recovering from long COVID or managing an autoimmune disease? Are you studying for finals? Are you rehearsing for a Broadway show?

Pausing to assess the needs for your chosen activity is one way of aligning your nutrition with more clarity and satisfaction. Our heavy-thing-lifter needs more protein; our exam-taker needs more carbs; our mom needs more sleep, and more, period. But an even deeper pause might allow you to question whether these activities themselves are acting as the right kind of majja for your life—filling you with purpose and prana. Are you living in an alignment that allows your prana to circulate out into the world according to your truth?

We can’t do what we love 100 percent of the time. A kid in school might rather be playing or hanging out with friends instead of studying for a chemistry test; studying is important, but in a way, we might have taken some of the prana out of childhood by requiring so much responsibility from young humans who have underdeveloped majja. It’s a different story when an adult, with more agency and a more mature majjavaha srotas, is studying for med school exams, for example. It will be hard no matter what. But if their heart is in it, the hours spent memorizing and dissecting will be meaningful, even exciting. If their heart is longing for something else, no matter how much attention they give the material, no matter how many carbs they eat or coffee they drink to try to supercharge their brains, “being a doctor” will neither stick nor flow. And even if it does, for a few moments or on occasion, the satisfaction of accomplishment won’t go past the brain and into the heart-mind. The cup will remain empty.

As this chain of gross and subtle nutrition illustrates, we cannot think only about what’s doing the filling when it comes to our sense of wholeness, satisfaction, and well-being. Majja without asthi, medas, mamsa, rakta, and rasa is nothing; so, too, the various things that can fill our cups offer no value without the cup itself. As I listened to the retreat attendees, and reflected on my own cup-filling endeavors, I wondered whether we always need to be full—whether smaller increments of emptying and replenishing is really what we’re made for. I also wondered why no one was talking about tending to the state of the cup. Is it dirty—with layers of coffee and tea and lemon water and dust building up and distorting our sense of taste? Is there a crack or a hole in it, making it less reliable while silently leeching all of your prana despite your best efforts to stay full? Is it just not your aesthetic, so you aren’t drawn to tending to, or filling it, and totally forget to drink?

In shifting attention to the cup, the vessel of our prana, the solid structure of the physical body obviously comes to mind. We know all the things that make us feel well and vibrant, and they’re not so hard: food, sleep, connection, sense-care, movement. Yoga retreats—but the daily version, aka dinacarya. But our body is only one expression of this stability—the gross kind. The mind, too, for all its inherent dynamism is capable of and requires stability. As metaphorized in the Bhagavad Gita, the manas functions like reins that bind horses (the sense organs) to a chariot (the body, being steered by Buddhi, or the thinking mind). If the reins are flimsy or dry-rot, we won’t get anywhere even with the clearest sense of direction. Least material of all, the spirit, is maybe the most stable facet of our Self. Described as “unchanging,” the Atman is where the essence of the Self resides. When we practice yoga, we are seeking a posture, an alignment, that both allows Atman to shine its light of wisdom and belonging, and a posture that allows us to be filled with that light.

On the last day of our weekend retreat, I received a soothing image in meditation that gave me the resolve and confidence to work through a conflict that felt like it was suffocating me. This kind of experience is what we all seek from retreats—or vacations, or spa days, or your version of cup-filling renewal. But it doesn’t have to happen periodically. It can happen every day—20,000 times a day, in fact. With each breath, we fill and empty our cups. With each breath, we bring more integrity to our cups themselves. With each breath, we patiently, lovingly fill in the cracks and holes and chips that inevitably arrive with the care of a kintsugi artist. Giving our precious attention to this alchemy, we drink in our own magic and retain the golden light of high summer even as autumn’s darkness descends.