Whenever I was nervous about a test, presentation, or performance as a kid—which was every time I had a test, presentation, or performance—my mom would tell me before dropping me off for the Big Thing, “You’ll do great, Jenny. I feel it in my bones.” Depending on my mood (and age), I’d either let this warm reassurance wash over me, or I’d dismiss it as unfounded mom-hype that said nothing objective about my preparedness or worth. The “feeling in her bones” didn’t account for the hours I’d spent studying or memorizing or rehearsing; didn’t account for the possibility that I’d totally blank out in a stress spiral once I got the booklet in front of me, stood at the podium, or assumed position in the cloud of vanilla-scented fog rolling over the floor of the darkened stage; didn’t account for the chance that I’d be asked none of the questions I knew by heart and instead evaluated on my ability to improvise. In other words, her “bone feeling” lacked the certainty—the knowing—I needed and sought through all my preparation. And even though my brain is perfectly built for the American education system’s evaluation methods, and even though I experienced time and time again an invigorating tunnel-vision of focus that blocked out all distraction from my senses except for the gentle throb of blood rushing into my small ears (purple ears became my secret sign of a test well-taken) when I entered such high-stakes situations, I didn’t trust myself to rise to the occasion of putting my passions, my knowledge, on display.

Almost 20 years later, I can’t say for certain that I’ve ever experienced what my mom described as feeling something in her bones. The phrase always suggested to me something deep and solid—a steady state of prescience, of knowing-the-outcome, that existed fully formed and capable of coating her anxious child’s heart with sneha. I’ve always considered myself to be too unsettled by nature to have such bone feelings. Anything I might experience in the same category—that of intuition, of choiceless-choosing—bore the felt sensation as dynamic, can’t-ignore movement. A restlessness in the heart and belly; that sudden wave of nausea or titillation of desire or tidal wave of thank-God relief. Nothing stable or steady or prescient about it. Only a clear(er) direction for my next move, one that required less deliberation or effort. An open path. A spaciousness. A wind at my back.

This wasn’t the nature of bone, from which I extrapolated a forever of never quite knowing where I’d end up, an inherent flaw in my brand of knowledge that required so much constant effort and repetition. So much forgetting and remembering. So much falling and getting back up. If they weren’t already broken, surely my bones wouldn’t last long under these conditions.

“I thought of walking round and round a space

Utterly empty, utterly a source

Where the decked chestnut tree had lost its place

In our front hedge above the wallflowers.

[…]

Deep-planted and long gone, my coeval

Chestnut from a jam jar in a hole,

Its heft and hush become a bright nowhere,

A soul ramifying and forever

Silent, beyond silence listened for.”

—Seamus Heaney, “Clearances: VIII”

On the surface, my mom and I look and behave as differently as the variety of our bone feelings. But as my sister, astute woman that she is, likes to point out, this coconut didn’t fall far from the tree. My mom and I share more traits than I sometimes care to admit; and even as our seemingly-opposite personalities have traded places over the years (I’m the steady, intuitive one now . . . I guess it’s all the yoga and ghee?), we complement each other in just the same way. This also goes for our bones. At least, metaphorically (mine have already started deteriorating, while hers have somehow increased density post-menopause . . .). The seeming contradiction in our two experiences is bone-deep knowing is precisely how Ayurveda describes the function and structure of bone, or asthi dhatu, the channel of which will be our topic for the month of September. I threatened repeating this to the point of meaninglessness at the beginning of the year, but I’ll say it again: asthivaha srotas is maybe my favorite channel, and one I’ve been looking forward to teaching all year, especially during the summer months. During pitta season and while teaching the dynamic srotamsi of rakta (blood), mamsa (muscle), and medas (fat), I was a stranger in a strange land. Working through those concepts and ways to share them through yoga was a challenge, and like any challenge has made me a better teacher for sure (and given me some ideas for next year’s themes). But I wasn’t at home in those practices. I’ve come into a deeper relationship with my constitution and how to tend to its reliable needs this summer, regardless of the environment, and how to maintain health according to the parameters of my reality. (We can talk more about that cryptic notion if you want; comment/chat ⤵️.) And so the teacher learns.

In a certain way, my (failed) experiments in pitta-management were an excellent segue into vata-land, which announces itself upon September first with those recognizable sighs of relief, for the structure and schedule that will spread aloe over summer’s chaos, and of nostalgia, for the window of endless play that’s closing along with the windows we might need to draw down lower in the chill of brisker mornings. There’s a familiarity to the quickened breath of a new school year, the excitement of what you’ll learn and experience mixed with a dread of falling short. All shot through with the wafting aroma of new notebooks and the sweaters you had tucked away all summer, each fall laying down another layer of beginning that is simultaneously an end.

Bone is that way, too—full of contradictions that, as the “trending” conversations about bone health all around the internet have proven, create madness and controversy even while ostensibly relying on the order and logic of science. We’ll get to that unwieldy topic of bone density, hormones, and aging later, but before that let’s zoom out and put this conversation about asthi in the wider context of our year-long study of the channel systems as a lens through which to achieve mental clarity and resilience.

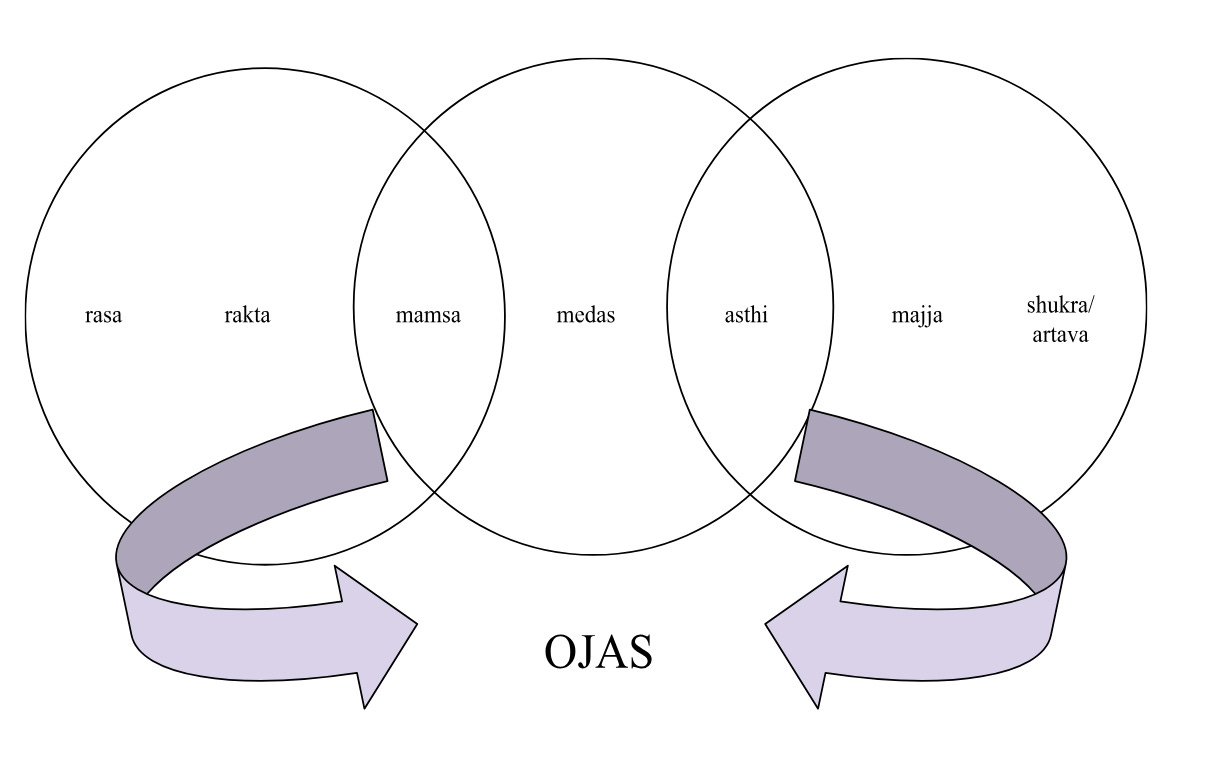

As I gestured toward last month, asthi brings us into the deepest, most subtle trifecta of dhatus (tissues) as described by Ayurveda. These final three dhatus, and their associated stromasi, that will close out our year are the most challenging to make changes to, but also the most easily affected by mental disturbances (aka, stress and all its shades and shadows). While the more superficial tissues are inherently dynamic in nature, more readily depleted and replenished by food (digested food, that is) and its essence of prana, these “core” dhatus require stronger stuff to receive nourishment, let alone “grow.” Ayurveda’s laws of nutrition offer a logical explanation for this: each tissue passes on nutrition to the next layer after satisfying itself, so the deeper you go, the denser, more penetrating, and more refined nourishment you need. Since the more superficial layers are inherently involved in survival, aka the stress response/sympathetic nervous system, their nutritional needs will always take precedence.

Our deeper tissues are the stuff that offer us stability and structure long-term—in our lifetime and beyond—but if we’re not alive, as in now or tomorrow, then the future means nothing.

At the border between circulating and longefying tissue, bone occupies a tricky nutritional zone. Its direct source of fuel is medas (fat), but it’s also heavily affected by the whims and intensities of mamsa (muscle); both of these greedy/hungry tissues can easily dominate asthi despite their inherent codependence. When we think about movement in general, especially strength, we often focus on mamsa. Muscles are what do the moving—contracting and relaxing and all, over and over, isometrically and concentrically and eccentrically, in elegant synchronicity and (thankfully) without our conscious commands. My typing right now is the result of dozens of muscles coordinating to execute the will of my mind, ingrained in my tissues through repetition the mind-in-body known as “muscle memory.” Add to this the way muscles assert themselves in space, creating curves and patterns of all sorts that have been ingrained in our collective consciousness as “good,” “healthy,” even worthy of eternal artistic glory.

When fitness instructors demand that we SQUEEZE and PULSE and PUSH HARDER!!! for ONE MORE SET!!!!!!, or in the gentler context of a yoga class “to hug the muscles to the bone,” we’re actually creating an internal conflict that is antithetical to strength—and the freedom of movement we’re trying to create in bone. Muscles do the moving, but do we ever think about what is being moved? Bones are being moved. Literally, any movement we perform, from walking to squatting to sun saluting, is about transposing our otherwise static bones from one location to another. Through space, through articulation at a joint, into different relationship with gravity.

Not only are they the objects of movement, but bones are the directors of movement. The longing to move and be moved is built into the structure and function of the asthivaha srotas in the form of prana. Along with the brain, heart, blood, and colon, bones are one of the main receptacles of prana in the body as described in the Ayurvedic texts. These sites also share a special relationship with the vata dosha, which governs the movement principle in all of the universe. Whether whizzing by in thoughts or hormone cascades, transporting oxygen to cells, extracting energy from food and eliminating toxins, or expressing our human-ness in the unique structure of our upright, spine-based, front-facing skeleton, a stable structure defined by curves and spaces, vata and prana are the conductors of the symphony of our lives—and the very rhythm that they maintain, and bend into the kinds of syncopations that summons us to dance. As the classics assert, no bones about it:

Vāta in its normalcy maintains the whole body and its systems, working as prāṇa, udāna, samāna, and apāna. It is the initiator of all kinds of activities within the body, the controller and impellor of all mental functions, and the employer of all sensory faculties (helping in the enjoyment of their subjects). It joins the body tissues and brings compactness to the body, prompts speech, is the origin of touch and sound, is the root cause of auditory and tactile sense faculties, is the causative factor of joy and courage, stimulates the digestive fire, and helps in the absorption of the doṣa and ejection of the excretory products. Vāta traverses all gross and subtle channels, molds the embryo shape and is the indicator of continuity of life.

[…]

Vāta is indivisible and is like an eternal god with no origin. The existence and destruction of all the creatures and their happiness and grief depends on vāta. It is the God of death, is the controller, regulator, and the lord of all creatures, Aditi (the first one), Vishvakarma (creator of the universe), is vishvarupa (omniform, or with innumerable forms), sarvaga (omni-pervading), the regulator of all actions and thoughts in the universe, is subtle, and is omnipresent. It is lord Vishnu and permeates the whole universe. Lord Vāyu alone is God.

—C.S., Sū, 12/8

Asthi knows its stabilizing force in the micro and macrocosms (it doesn’t need to feel this knowledge in its bones, it is the very feeling), and seen in the sheer amount of time it takes to actually change the nature of bone in our bodies—at least six months, and that’s with a lot of diligence in one’s protocols. Bone will hold onto its nature because it knows that it relies on those unpredictable earlier dhatus to execute its will to live, its longing to move and be moved, to keep the body alive when the things that might cause them to actually break show up in the form of danger—so like a good dance partner, it lets muscle lead. But even the most patient partner can’t be denied access to its own source of nourishment forever; and without rhythm, the whole dance breaks down anyway. When muscle chronically starves bone, bone loses its hold on itself. That’s when we see the cascade of physical and mental health problems in the bone and beyond that are so hard to rectify—namely, because by the time the issue reached the bone level, the imbalance has been festering for a long, long time. Creating its own rhythm and structure that’s hard to break.

Here, we see one of the disparities in the nature of longevity as described by Ayurvea and yoga, as a basic definition of health, versus what’s laid out for us in modern health and medicine. The decrease of bone health, density as well as mobility in general, would seem to naturally occur with age—even if muscle has been sharing its food nicely with the whole system for decades, eventually the capacity of the system to hold loosens and weakens. Hence why we describe the post-menopausal decades of life as the “vata” period—it’s not a disease to have weaker bones, but a shift in our physiology.

Ayurveda’s approach to handling the cascade of changes that happen in menopause—to bones and everything else—isn’t suppression of the change, or an attempt to reverse the relentless march of time so as to preserve the function of the body as it was decades earlier. Rather, it’s to minimize the intensity of the changes, slow down the process, and meet the new conditions with appropriate support systems. To protect the system from unnecessary accelerations in age—i.e., building barriers to block the winds of vata from knocking down the house. If bones might be weaker when we’re older, we don’t force them to “build up” which requires challenging a system with lower digestive capacity and potentially poking the mamsa-bear that will gobble up the food for itself. We minimize the risks to the more fragile bones by reinforcing structure from inside. Rather than walking around with weighted vests strapped to our body, increasing the load of gravity on our bodies and minds with a constant felt reminder of our bone-deep fragility and impending death, we might benefit more by lying down on the ground and resting with the weighted vest on our bellies or thighs, breathing. We lubricate the joints, through movement/circulation and abhyanga, to minimize dryness and friction; we minimize stress so our blood doesn’t leech calcium from our bones prematurely or in excess; we strengthen our capacity for balance so we’re less at risk of falling; and since we know we will probably fall anyway, we give the body many different kinds of challenges so we keep learning new ways to fall and stand up again. And repeat.

This strength and resilience doesn’t come from bicep curls or even squats. It comes from a strong, supple, faith-ful mind.

While they look as opposite on the surface as my mom and me, bones and the mind are the gross and subtle sides of the same coin. Both are inherently mobile and thereby imbued with vata and prana (bone is the only tissue governed by vata, in indirect proportion; only blood is governed by pitta, and the other five dhatus are governed by kapha, all in direct proportion). And both respond very well to the kind of supple containment achieved through repetition and rhythm. Think: Temple Grandin’s squeeze machine; a weighted blanket; a verbal hug from your mom telling you you’ll do great on your chemistry test or at your dance recital. The dualistic union of structure that holds movement, making it functional and purposeful and sustaining of life rather than destructive of it, is the very purpose of asthi in our Ayurvedic anatomy.

Dhatu

- Function: Support, protection/dhāraṇa, protects vital organs, structure

- Upadhatu: Teeth (danta)

- Mala: Hair (keśa/ loma) Nails (nakha)

Srotas

- Mula: Pelvic girdle, sacrum, medas dhatu, buttocks

- Marga: Skeletal system

- Mukha: Nails, hair

Some of you out there might recognize this word dharana from Patanjali’s Sutras—step six on the eight-limbed path of yoga. In the context of yoga, dharana is the stage of meditation in which one’s attention is “held” by the object, but not yet fully absorbed into the object. Curious, that asthi dhatu is in the same position, five out of seven in the list of dhatus, or out of eight if you count the culmination of ojas. The movement of the mind has been fixed, but is still distinct as its own self. Curiouser, like how the arrangement of our bones creates our unique shape/stature/physique and movement patterns as individuals, and are the last part of us to decay after we die. Curiouser and curiouser, that our innate fear of death, the klesha or “obstacle to enlightenment” known as abhinivesha, is held deep in our bones—the fear of death, or “clinging to/holding onto life,” of losing our unique identity that is the manifestation of our will to live.

Curiousest: that in untethering ourselves from the fixity, rigidity, slowness, and seeming permanence of bone—of the identity known as Ahamkara—we actually liberate that will to live in its universal form and become it. The satisfaction of our deepest desire is bound up in the steady growth—and breaking down—of our bones. Even the supposedly “dead” byproducts and exit points of asthi—the hair, nails, and teeth—are, according to many traditional myths, the greatest sources of our energetic strength, that which we loosen our hold on at our peril.

“My thin, ungainly body and my rather ungrounded life had acquired serious aplomb with the appearance of my new teeth. My luck was without equal, my life was a poem, and I was certain that one day, someone was going to write the beautiful tale of my dental autobiography.” —Valeria Luiselli, The Story of My Teeth

Hastening our bodily death to arrive at the vastness of spirit is not an option for resolving our conundrum of ego; that sounds more like a plan mamsa might come up with 😉 Rather, we look for ways to engage with prana and our vast potential Selves while alive, sentient, and embodied. Enter the breath. The great medicine for bone, for vata, and for the mind. Breathwork is one of the ways that yoga practice can actually support bone density, not the “loaded” asanas that have been falsely purported to “build” bone. By activating our parasympathetic nervous system and toning the vagus nerve, rhythmic, yogic breathing reverses the spiral of stress that will turn mamsa and its predecessors into food-thieves, strangling and starving bones, confusing our hormones, and hastening the aging process and vata-pocalypse we all feel, in our bones, is coming for us and will do anything to move out of the way of. By connecting our conscious awareness to breath, we set the conditions to keep the prana circulating in our systems rather than letting it leech out into the world via our senses more than it needs to; through breath, we can be moved by the immortality of spirit without having to die for it.

While I was tempted to direct us toward a more focused pranayama practice this month in service of this experience, it seemed like we were skipping an important step. Jumping into the vast well of prana, silent and alone, would be the equivalent of moving from 80 and sunny to 30 and blustery; and while that might happen, this fall or sometime in the future, we don’t have to jolt our systems out of their expected rhythms of seasonal transitions if we can help it. And so we can occupy another transition zone—of sensory perception and action, of body and mind, of mind and spirit—through mantra.

Though asthi is associated with vata, which is air and space elements, my teacher Dr. Scott Blossom once clarified that the nature of asthi is fire. Bones are acted upon by the heat of mamsa, and are “filled” with the subtle transformation and transmission of information that occurs in the marrow (our topic for next month). And as described earlier, the depth and penetrativeness of nutrition needed to reach asthi—and hence the agni that will digest it—is great. The prana stored in asthi has an inherent heat to it, which when circulating well and properly we don’t pay much attention to; but when prana stagnates, the ensuing inflammation becomes hard to ignore.

I like to think of mantra as the fire that illuminates the truth of pranayama—the lure that brings us deep inside the subtle energy of bone and holds us, captive and captivated, there. An advanced practitioner’ mind may be able to be “held” by the movement of the breath alone (or by its temperature, for that matter), but for most of us it’s too easy to get lost, to have our lantern extinguished or die out, in pure breath. Because it has words with meaning (even if you don’t know the meanings, and because those meanings can be registered by both the thinking and feeling minds, as “words”/ideas and as energy, respectively), mantra gives the mind something to hold onto while it remembers its rhythm, in order to forget its identity and detach from the thoughts that distract from the wholeness of the Self. When my teacher Kate O’Donnell first described how mantra could “interrupt” thought loops—you’re walking down the street, ruminating over an argument or to-do list, and suddenly your mind shifts to the OM channel—I didn’t believe her. I’d had some lovely, transcendent experiences at kirtans in the past as well as while singing in choirs, but no regular mantra practice; I believed no mantra could be a match for the gale-force winds of my mind’s vrttis. But just like my belief that my body couldn’t possibly benefit from ghee, I was proven wrong after the first taste of this powerful medicine (bones, and minds, really love ghee, too . . . just saying). After just three days of a very simple mantra meditation, the insomnia I suffered from this winter disappeared—along with my coffee addiction. In recent weeks, when the insomnia came back along with a thorny interpersonal conflict, my mantra practice stood up tall and proud in my mind—not necessarily a solution to or distraction from the problem, but a stepping stone toward listening to the right solution, not the first yelp of reactivity and fear. The intensity knob on the situation turned way down once I started turning the channel of my mind to my chosen mantra whenever I’ve drifted into shame-spiraling rumination. I feel the same way I did when my mom said her bones felt that I’d be okay—but this time, I hear my own bones speaking. And I know they’re right.

“Our connection to earth, and our sense of ground, is found not only in bone but also in the deep spiraling of our inner ear.” —Liz Koch, Stalking Wild Psoas

And as we approach the tipping point of our earth cycle at the Fall Equinox on September 22 (subscribers, look out for a special full-length Equinox yoga practice that weekend), we’ll practice falling with skill and grace so that we don’t shatter our bones when we meet the earth, but allow them to be held and fed by the Great Mother—who never merely knows, but feels, Her wisdom; who somehow finds a way, unlikely as it may seem, to remind her children of the Truth that they’re just like Her.