“be softer with you.

you are a breathing thing.

a memory to someone.

a home to a life.”

― Nayyirah Waheed

When I set out to teach about the srotamsi, the Ayurvedic channels of the body, this year, I was pleasantly surprised (though maybe I shouldn’t have been!) when the order of the channels in which they are taught (and progress physiologically) mapped out well over the seasons. This high-level organizational container was about all my vata-brain could handle back in January, and I trusted that the details of my teachings would arrive each month in a relevant and exciting expression without my having to over-prepare.

But there was one month that gave me a little more pause than the others, that made me doubt whether, and with what, the muse would strike when the time came to teach that srotas. A problem for future-Jennifer, I resolved, and launched in without tripping over that hypothetical speed bump. Well, we’ve arrived at that month—where I’m teaching about the medovaha srotas, or the channel of fat—and I’m confronting the challenge that I saved for then-future-, now-present-Jennifer, to deal with.

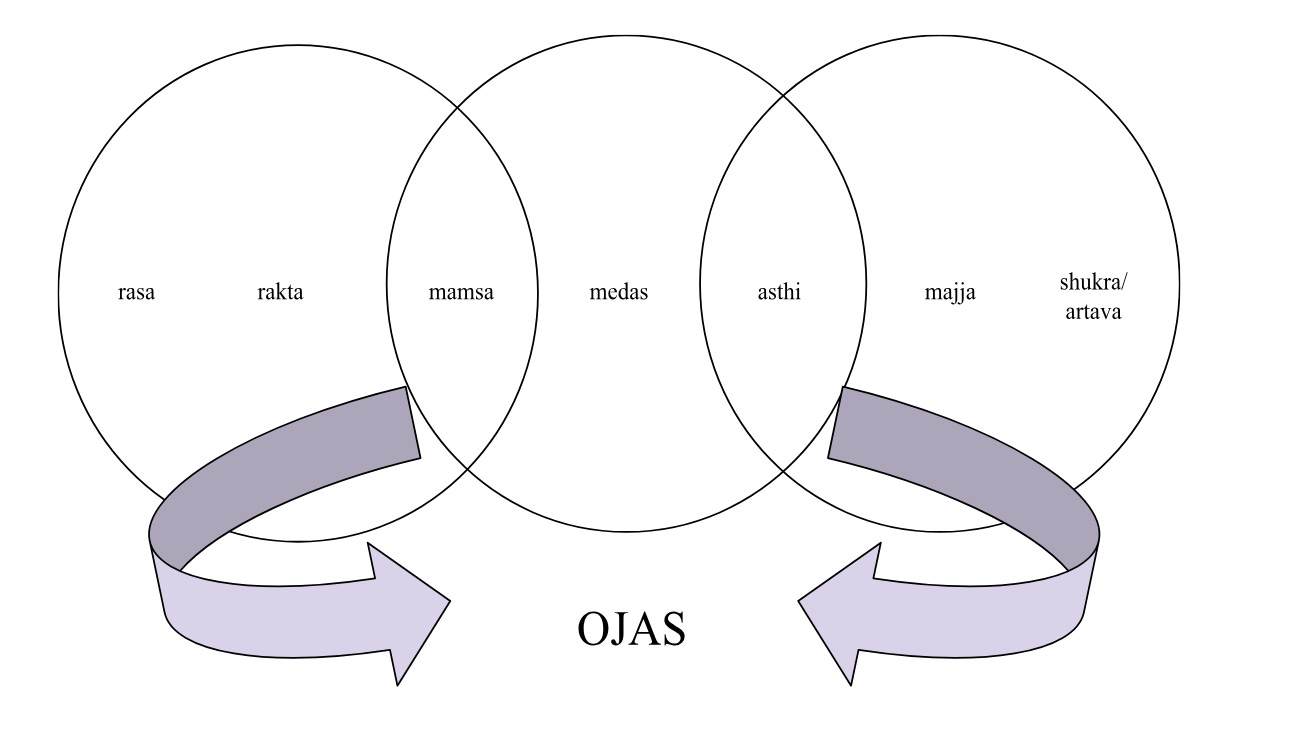

Fat is a word that elicits strong emotions in most people, including me. From health and diet culture, to fashion and (now, somehow?!?) religion-infused conservative political movements, fat has acquired a big reputation across the spectrum from hatred and disdain to “positivity.” And rightly so: when we look at fat through the Ayurvedic lens, it’s a dhatu (tissue) whose very job is to promote the kind of attachment that’s hard to budge, physiologically and psycho emotionally. Medas dhatu moves us into a trifecta of deeper tissue layers that solidify (literally) our identification with the gross body—the parts of us that grow, take up space, and move. It’s fed by the more superficial tissues that circulate through the entire system, and which are easier to “share” (think: blood transfusions for rakta, IV drips of saline and electrolytes for rasa) and change in their quality and quantity pretty regularly. Medas then feeds the next trifecta of even deeper tissues (which we’ll learn about this fall) that are much harder to access and change, even with persistent routines and health/medical measures. These innermost structures give us shape over longer periods of our lives—including beyond our death, in the form of reproductive and genetic material. Medas, then, is a most vulnerable layer of our Selves that engages external and internal relationships, where the past and future collide in the present. It’s where we are most sensitive to others’ gazes and to our own gaze—and where we have the opportunity to practice compassionate Self-awareness with the greatest challenge and reward.

Part of my long-term health journey has been about befriending medas dhatu, and occupying this very central aspect of my whole-Self health without guilt, shame, and, most of all, fear. Through my struggles with food and exercise, I’ve ruined a fair number of holidays and social events by contaminating spaces of love and togetherness with an obsessive preoccupation with avoiding fat. And through this denial of the function of fat per Ayurveda, snehana, I found myself in a state of mental and physical isolation and disintegration that required the very thing I thought I could avoid forever through a health regimen of strict discipline and self-sufficiency: dependence on others. Thankfully, I was able to receive enough snehana in a variety of forms to return me to my senses and reaffirm the center of my being. Much of that ongoing work has manifested in changes to my health in the last year or so that have given me the confidence to share about these parts of my past at all, let alone teach from them. And so it seems like then-present, now-past Jennifer had a better handle on what I’d be capable of in sharing an approach to clarifying and nourishing the medovaha srotas, than I have her credit for. (She must have just made a nice batch of ghee.) So let’s begin.

While there’s much to say about the constantly evolving “science” around the health of fat for our physical body from a nutritional standpoint, I’m going to say right off the bat that we’re not going to go there this month—on the (digital) page or on the mat. With the way diet trends pendulum between extremes, the very individual nature of people’s nutritional needs, and the fundamental differences between Ayurvedic nutrition guidance and mainstream nutrition, it’s just asking for confusion, misinterpretation, and unnecessary harm and worry. All I’ll say is this: you should eat fat, not too much, every day. Like all food. Like all things. As the middle-most dhatu, medas epitomizes the ethos of moderation and middle-path living. If you need more specifics, we can talk and draw up a map for you together.

Instead, we’ll keep our discussion within the terrain of the relationship between medas and manas (the mind), the direction we’re spiraling closer toward as we progress through the year. From a purely seasonal standpoint, medas is indeed a perfect theme for our late-summer moment. It was just the other day, it might have been August 1 exactly (coincidentally, the Celtic feast of Lammas, or the celebration of the harvest/grains/bread), that I sensed the shift I’ve been longing for for weeks as my area endured an unprecedented stretch of heat and humidity. During this time, I spent more time than I wanted to up in my “lair,” the only room in my fifth-floor apartment with air conditioning, curtains drawn, fan blasting, and ice pack tucked behind my bra at my mid-back. I wondered when I became such a wimp, unable to handle the summer. Then I realized that this wasn’t like any other summer I’d lived through, and my slow-to-evolve body probably wouldn’t ever get used to this heat in my lifetime. And so we adjust—and wait for fall, and rejoice when it arrives.

Don’t get me wrong—I know that temperatures will climb back up between now and October. But waking in dusk-darkened light, being able to walk 10 minutes outside without needing a change of clothes, and noticing a slightly deeper azure in the sky, I’m certain that we have tipped into the season of vata sanchaya, or accumulation. Technically, this has been happening since the Summer Solstice, but the light and heat have been too dazzling, and the beads of sweat and swollen ankles too distracting, to notice that dryness has been slowly building in the system. Through all that loss of physical hydration, and the longer amounts of daylight, microcosms and the macrocosm move closer to the season of vata which each beach-day and BBQ. While a little dryness can feel like a relief after the surges of cool-damp in spring and hot-damp in early summer, dryness is generally not a state we want for our bodies (in excess). Like your houseplant you forgot to water before your vacation, or the fresh basil you left to hang in a sunny window that desiccated before it could become the pesto of your dreams, dryness in our tissues—and in our mind—equals, more or less, death.

Enter fat. The dhatu-form of kapha dosha (made of earth and water elements), fat is the antidote to dryness, and to vata more generally (with a few caveats). From ghee and ojas milk, to abhyanga and nasya, fats are what keep vata-types and the vata-deranged (yep, that’s the technical term for a state of high vata) from drying out and floating away—into higher states of consciousness (in best-case scenario), or into physical and mental disintegration and delusion (in a worst-case scenario). A seasonally-oriented diet for mid/late-summer would include an abundance of healthy, plant-based fats (and a moderate amount of liquid animal fats). Think: avocado and coconut, takra and milk, appropriate to one’s state of agni. Generally speaking, fat, while a “denser” tissue from a dhatu perspective, is less “dense” as a food than proteins that feed muscle, making them easier to digest and a more available source of nourishment as we start to prepare for the colder months of fall and winter. Even the sources of natural sweetness that abound in summer—juicy fruits and veggies, and the grains celebrated on Lammas— contribute to medas in their own way; they’re described as water-based foods in Ayurvedic nutrition (madhura rasa), and as we all know carbs can be stored as fat in the body when not used immediately for energy.

The word I shared earlier that describes the function of medas, snehana, explains its balancing effects on vata. While there’s no one English word that snehana translates to, a superficial meaning would be “oiliness” or “lubrication.” Obviously, this is what fatty substances do and feel like—to the skin, the joints, door hinges, etc. On a deeper level, snehana means something like “cohesion.” Not to offend any vegans, but the marbling of fat in meat (essentially, muscle/mamsa + fat/medas) illustrates this connotation. But it also refers to a more energetic cohesiveness for the whole system. As one of my revered teachers recently elucidated, snehana is what holds cells together—within themselves and in the structures they combine to form. It’s that deep, that essential, that mysterious.

Snehana also means “love,” specifically “mother’s love”—the kind of love that moves two people into a state of divine union, that moves a woman to sacrifice her body for the sake of her child, that maintains the electromagnetic heart-field between mother and child even once their bodies have separated, grown apart, and increasingly individualized through time and space. Indeed, the anatomical space in which this kind of love manifests—in the womb—is one of the “roots” of the medovaha srotas. The apron of fat that wraps around the low belly and back, the bane of most women’s existence, called the omentum is a storehouse of the fat cells that support a steady flow of reproductive hormones required for building and maintaining life—that of a potential child, and that of the mother herself. We’ll get more into this A&P later, but the muffin tops, spare tires, and “pooches” that we’ve been taught to despise, to crunch and ab-roll and plank into hard, flat, submission, is the literal stuff of our existence. It’s the layer of love—the cohesion—that made us, us.

Supporting the health of this dhatu and its channel requires a combination of opposites appropriate to its central location in our gross and subtle Ayurvedic anatomy. We need just enough nourishment (brhmana/yin) to keep it juicy, and just enough stimulation (langhana/yang) to be able to digest that nourishment. I’ll speak for myself in saying that this is the place I find myself most Augusts, especially this year. Having worked through a near-final, umpteenth draft of my book, offered my annual service to my teachers by assisting retreats (which rejuvenated me, too), made up for work I missed while traveling, and endured the daily slog through 90+-degree weather, I’m ready to hit pause and relish in a state of easeful contentment that usually describes both kapha and medas. I’m not totally burned out (which is common by this stage of the summer), but I can glimpse that edge on the horizon if I try too much in any direction. And I am not interested in meeting or pushing that edge (been there, done that). Things are percolating for fall, but they need a bit more time to sun-ripen before harvesting and launching. Right now, I’m happy to monitor their growth, feed them with water and attention and singing, and support our mutual snehana.

And that’s what we’ll be doing on the mat this month, too. As most of you who practice with me know, I plan my classes—if not all the sequencing, then the framework of the srotamsi, as I’ve been leaning against this year, or other themes/concepts I’m excited to share. I also like to leave space for in-the-moment requests from students in the room. Usually the requests are some variety of “hips” or “shoulders,” which fall into the sequence anyway so they’re easy to accomodate. But this month, I’m going to ask for a bit more from all of us—for snehana-style-co-creation. It will be a bit of a respite for me and my thinking mind, and a treat for you and your feeling mind. Letting the practice arise from the body and taste and feel delicious—like the perfect slice of watermelon, matcha latte, or ice cream that by August you have no inclination to deny yourself.

I know that not everyone is comfortable sharing their movement-cravings in class, and sometimes (like in my beginner classes) people don’t even know what they want. Many people come to class to be told what to do, to give themselves a break from all the decisions they’ve spent all day (all season, all year, all their lives) making. I get it. I usually want some version of that, too. So I have a strategy to bring us all into a medas state of mind, a state of inner-snehana where those “decisions” are not top-down but bottom-up—choiceless choices, if you will.

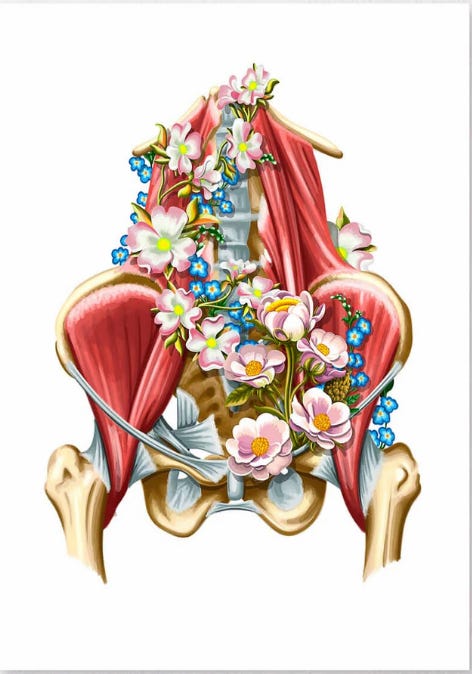

I’ve recently been entranced by the incredible work of Liz Koch, a movement educator whose book Stalking Wild Psoas I’ve been exposed to through excerpts and concepts for years. Last month, I finally read the whole thing and fell under the spell of this incredible, mysterious muscle-slash-sense-organ. While not technically “fat,” psoas embodies the essence of medas and snehana. Its sling-like structure invites the contents of the abdomen and pelvis—the territory of the omentum—to relax into its supporting flesh-hammock through a coordination of breath, digestion, and elimination. At least, it supports that physiology when its in it’s natural state of relaxation. A stressed psoas moves us into the contracted “ready” stance to fight, flight, or freeze—ready to rumble and protect our individuality. Gripping through the pelvis cuts of the supply of nourishment and energy we need to be, in the short- and long-term. Unfortunately, between our habits of prolonged sitting, sucking in our bellies, restricting our breathing, and generally living stressful lives (mostly out of our control), psoas tends to be more contracted than relaxed.

https://codexanatomy.com/products/iliacus-and-psoas-muscles-floral-white

Almost all aspects of yoga—from asana to pranayama to meditation to chanting—support a supple, juicy, psoas. We’ll lean into specific psoas work, though, at the start of class to make space for the inner listening required to co-create a practice. Think spirals, curves, undulations, long exhales. The kind of path you take home at the end of an August trip you don’t want to end. This is the kind of movement psoas allows and longs for—the ripples of self- and mutual-care that keep us held together despite all the ways the world tries to dry us up and pull us apart.

“Curling within, leaning toward, collapsing into, landing upon, and diving through are all gestures of return. They denote a vital longing to come home. When infused with awareness and intention, these gestures have the power to flood tissue with vitality, breathe song into bone, and spark a fire within a dry, vulnerable heart.” —Liz Koch, Stalking Wild Psoas (38)

Learning to trust a posture of relaxation, and the messages from the body for nourishment in the form of movement, food, rest, and relationships, is a practice unto itself that changes in its accessibility day to day. It’s my hope, though, that by softening into the strong, reliable, and resilient core of psoas, we can together start to trust ourselves—our True Nature, our inherent goodness and wholeness—with more confidence and enthusiasm. In a way, this style of teaching is much more in line with my own True Nature than the pre-planned version I’ve adopted since my schedule has become busier and fuller. So I’ll thank you in advance for cooperating with me in this indulgence of Self-Care.

If you’re not in Brooklyn, I’ll look forward to hearing your responses in the comments here on Substack to the question I’ll ask in my live classes: How do you want to move? Don’t answer as soon as you come to your mat; do a little rolling around, a little squirming, a little sighing first. Once the body has been softened up, the fascia fluffed and the psoas relaxed, you might hear an answer coming from a different part of your body—your Self—than you expected. Listen to the parts of you that need attention, and respond with the fullness of your Being. Be moved by, and for, your medas-protected core. Be fat, because you are a Being who is loved and loving.