Even

After

All this time

The Sun never says to the Earth,

“You owe me.”

Look

What happens

With a love like that,

It lights the whole sky.

―Hafiz

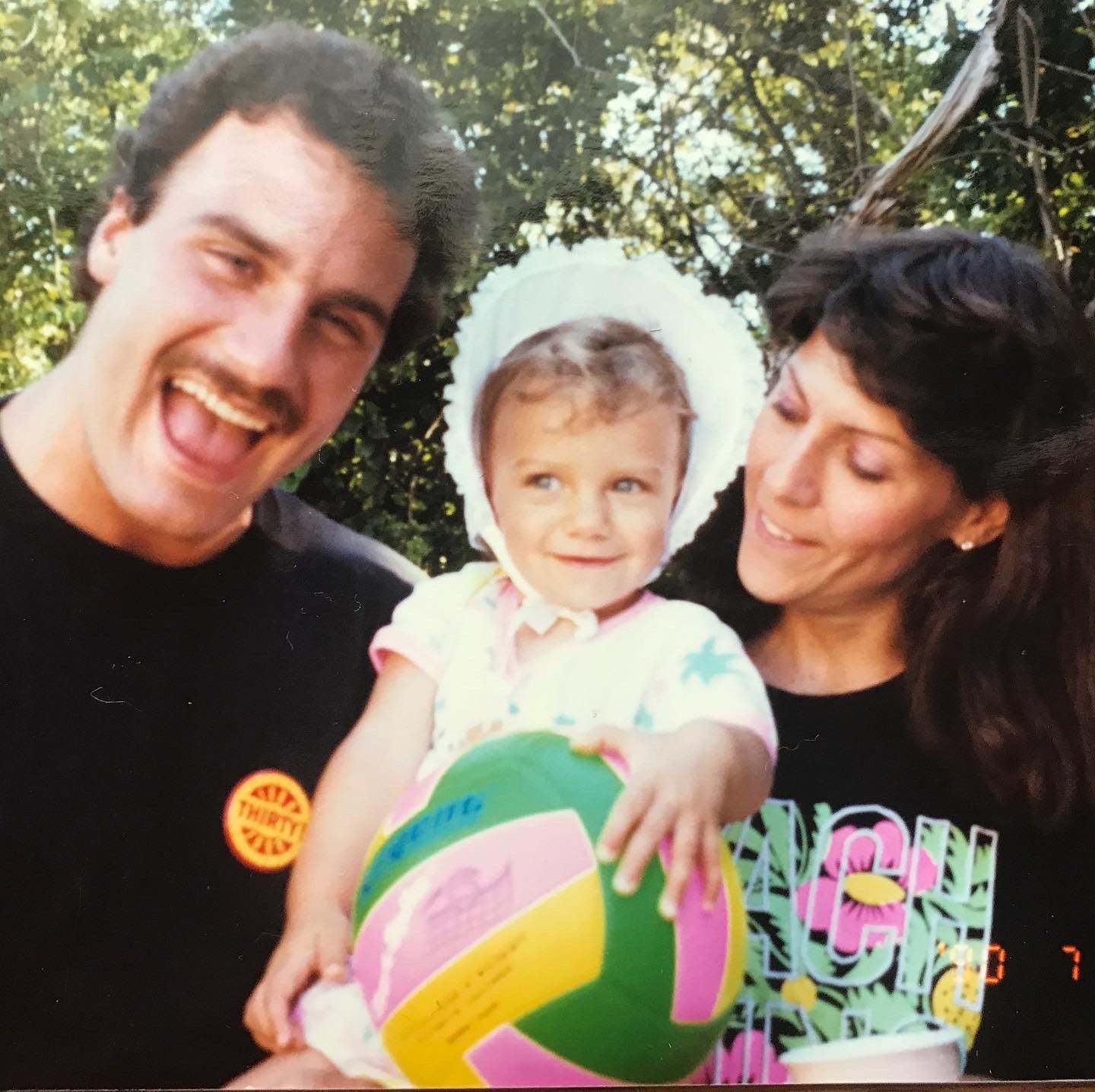

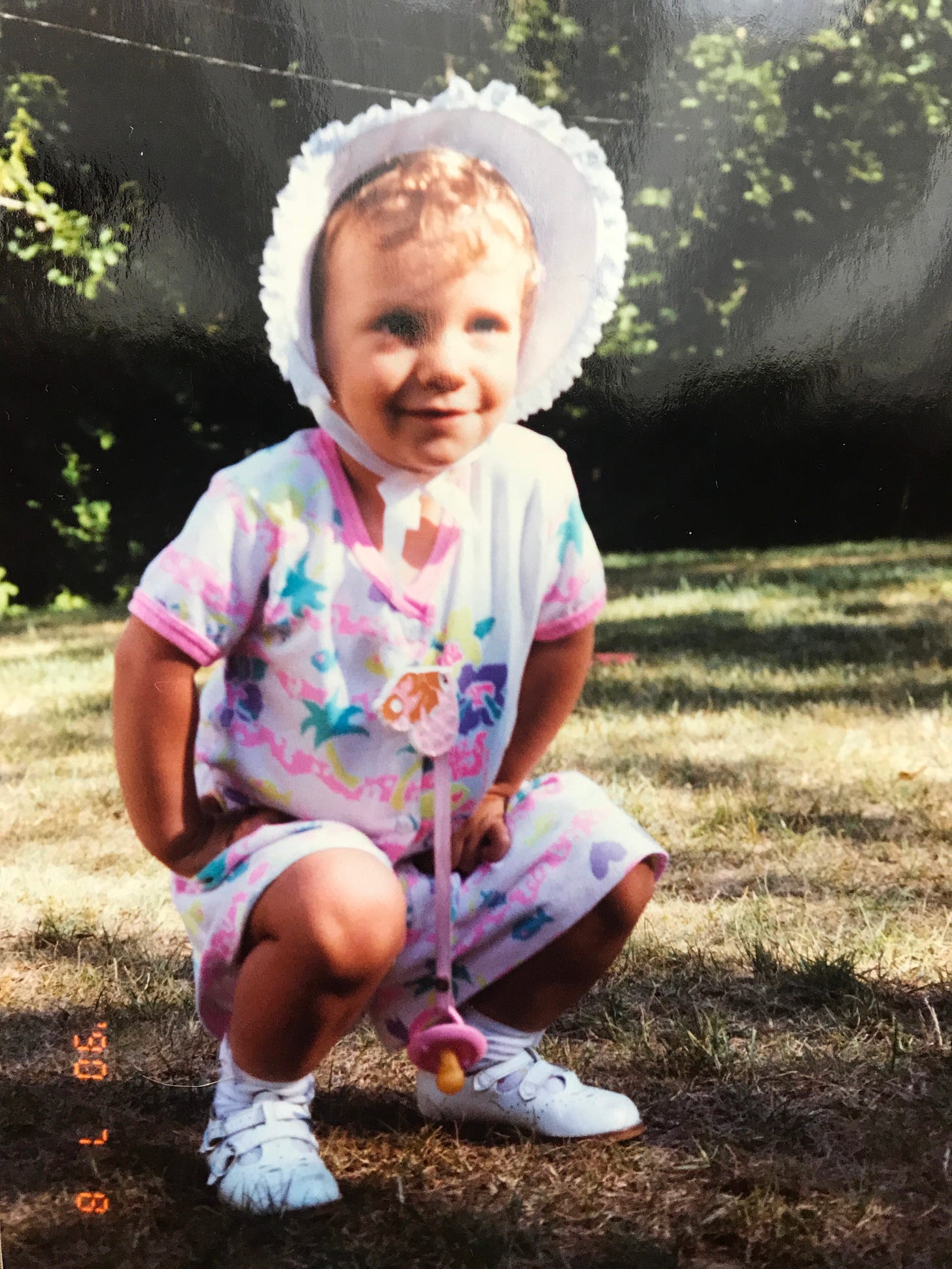

March has always been a busy month in my house. A succession of anniversaries and birthdays tangle into a knot of family gatherings, present-buying, cake, and flowers that always felt too close to Christmas to really enjoy. Growing up, when my birthday arrived in the middle of it all, I was always a little resentful of having to share the celebrations. I came to treat my birthday as part of a collective, and grew comfortable in disappearing into the knot (or slipping myself outside of it). None of this was really about or for me—not when we had a cake that was not my favorite with three names on it. Not when my little sister couldn’t wait a week for her birthday and had to get a gift on my day. Not when the start of Lent, Ash Wednesday, arrived around or on my special day, throwing me into a vortex of guilt—do I NOT make the biggest sacrifice I can think of (chocolate) so I could enjoy a birthday treat, or start off the season of inner purification by cheating on my promise? And worst of all, not when my elementary-school brain couldn’t understand that even though March was when spring arrived, it would never be warm enough to have a pool party in my backyard.

March been less tortured with each passing year, though no less demure. Living, and watching life not go according to plan, has made me see this month as a precious reminder of how we can’t take anything for granted. There’s no guarantee that I’ll get another year, so I take the chance to reinforce the love I have for others—even the ones who cheated me out of my own cake 😉 The intertwining of generations of love and beginnings on the calendar may be somewhat coincidence, but when I zoom out, I see it happening all the time, every day. Whether or not there’s a formal celebration, love is constantly being born, shining light on our individual selves and eclipsing them in relationship.

This is the energy of spring. And the energy of the srotas I’ll be teaching about in March: the purishavaha srotas, or the channel of feces.

If you had to read that sentence twice, then I did my job as a writer and a teacher by waking up your attention and getting you curious about how love, birthdays, and poop are related. I’ll probably say this every month of 2025, but this srotas is maybe the most important of all. Sure, we can’t “live” without prana, food, water, all our tissues…but without the proper function of this main channel of excretion (there are two more, coming up next in April—get excited!), our existence would be pretty crappy (pun intended) at the level of body, mind, and spirit.

For anyone with any exposure to Ayurveda, you’ll know that poop is maybe our favorite subject (after oil and ghee, which we mostly use to make sure we poop). Regular bowel movements are the number-one sign that our body is functioning. Before we go on, let me define what “regular” (or worse, “normal”) means when it comes to poop. The bowel movements should arrive upon waking, free of strain, pain, gas, mucus, blood, sticky residue, strong odor, and undigested food particles. Every day, not every four days—the ghastly definition of “constipation” per modern medicine. Poop is the very first part of our daily routine (after thanking God for another day of life).

A healthy person should get up (from bed) during the brahma muhurta (3-6 am), to protect his life. Contemplating on the condition of his body, the prson should next, attend to ablutions (after elminitng the uring and faeces). —Astanga Hrdayam, Su, 2.1-2

It’s the sign that our bodies have done a thorough job digesting the previous day’s food, emotions, information, and experiences, and therefore are ready to receive a fresh dose of all of that nourishment today. The texts state that if you don’t poop right away, you should go back to sleep until you’re ready to eliminate—otherwise, you’d be adding fresh food to a pile of compost-in-progress, creating digestive confusion and ama (metabolic waste). At the very least, you have some hot water and lemon (or another pungent substance, like ginger) and do some squats to get things moving in the pipes. And if there are any abnormalities about the poop, well, those are your instructions for what to eat, do, and not do for the day. A little loose? Skip the coffee. A little dry and pebbly? Add more ghee. Accompanied by a seranade of wind instruments? Chew on fennel seeds.

Paying attention to poop is not something most Westerners are used to doing. In fact, most people try to ignore it as much as possible—closing the toilet lid to flush to keep it out of sight and out of mind, or being too embarrassed to go anywhere but in absolute private. These denials of our poopy reality are one of the quickest ways to create an imbalance. Ayurveda describes 13 non-supressable urges—the adharaniya vegas—which all offer some kind of release of vata dosha: things like sneezing, crying, and, yes, popping. Keeping vata inside when it wants to move is like trying to catch and hold the gusts of March wind—it just doesn’t work, and causes more destruction than if you were to let them blow.

While what you put into the channels of nutrition affects the quality of feces, so surely does the integrity of the actual channel it moves through. The anatomy is fairly straightforward:

- Function: Nutrient absorption, strength, formation and elimination of feces

- Mula (root): Cecum, rectum, anus, sigmoid colon, and intestines

- Marga (channel): large intestine — pakvashaya (which means “the home of what’s been digested”; compared to the stomach, or amashaya, “home of undigested food”; and the small intestine, or grahani, the organ that “grasps” nutrients)

- Mukha (exit): anal orifice

As the end of the digestive tract, the purishavaha srotas (namely, the large intestine) is inextricable from everything that came before it—the annavaha srotas and, to a degree, the ambuvaha srotas, since water and electrolyte balance will affect the formation and elimination of stool. The channel itself is quite a remarkable structure. Inside the relatively small cavity of your lower abdomen is a tube about 5 feet long, which can hold up to 25 pounds of fecal matter (!!). And no matter how much poop is inside, the colon is also home to 38 trillion bacterial cells (aka, the gut microbiome). This is roughly the same number of “human” cells in your whole body—all concentrated in your lower belly. It’s a lot to ask of such a small space—kind of like living in a New York City studio apartment, or my crowded birthday celebrations.

The purishavaha srotas is part of the “digestive” tract, but what’s really happening is a post-digestive process since most of the nutrient extraction happens a little farther up in the small intestine, where the discerning gaze of agni can grasp and filter out the different elements in our food, then send them to the right place. Everything that we can’t use gets pushed along into the large intestine, where all those bacteria munch the remaining fiber (which we also can’t break down) to create gases (more vata) that support digestion and immunity. The walls of the colon also absorb any remaining water to make the final product, the gift of a healthy digestive process: formed, smooth, odorless stool.

The colon can get a bad rap when it comes to imperfect stool (and any kind of indigestion), since most of the time the trouble in breaking down food happens elsewhere in the GIT. Instead, the problems with the purishavaha srotas have more to do with the actual movement part of the bowel movement. The poop moves out of us not by our active pushing, but through the rhythmic squeezing of muscles called peristalsis (when we have to push too hard, things like hemorrhoids and fissures ensue…no fun). As with all movements of the body, this movement is governed by vata dosha. Between the significant real estate it occupies (space) and the importance of regular movement, the colon is a—the—primary home for vata dosha in the whole body. As such, regulating bowel movements will ultimately affect any manifestation of excess vata—whether it’s in the nervous system, the skin, other parts of the GI, the reproductive system, the lungs, the heart… Just think about the last time you had a really good poop—didn’t you feel great? Elimination keeps all of the vatas in the body moving smoothly and harmoniously, and happy vata leads to a happy life.

If vata is responsible for irregular movements of the bowel, the prana—vata’s more refined, subtle expression—is responsible for regularity. This is where we can experience the other ways a healthy purishavaha srotas contributes to our well-being. When the colon is functioning, it’s not just extracting water and giving our microbiome a snack—it’s also extracting prana, which is the subtle essence of our food once the more gross attributes (the different elements, which we might think of as macro- and micronutrients) have been pulled out in the small intestine. In this sense, the colon is absorbing—digesting—the most important aspect of what we eat. If the other parts of the GI tract haven’t done their job, we won’t be able to be truly nourished. This is one reason why the large intestine is paired with the lungs in TCM—both interact and supply our body with prana (or qi), the life force. Both are big spaces, the lungs being more yin because they receive nourishment (via prana vayu, the inward and downward movement), whereas the colon is more yang because it moves things (via apana vayu, the downward and outward movement). Often, imbalances in the lungs and large intestine are paired, too. When we have a cold or respiratory infection, we might poop a lot or none at all; when we aren’t pooping, we have to breathe more shallowly (aka stress). The body will do anything to keep its supply of prana regular and consistent.

In my yoga practices this month, we’ll be focusing on this interplay of the five vayus (movements of prana) as they affect purishavaha srotas.

The most important to keep happy is apana vayu (yay, squats!!), which will connect us to the rooting-down energy of the natural world in the spring that’s required for new life to grow upward (udana vayu). But the unsung hero of that down-up (or “root to rise” as it was called in my yoga teacher training manual), is samana vayu, the circular movement that takes place in the center of the body, in and near the GIT. Samana vayu gently (or not-so-gently) blows on the fire of agni to wake up our hunger; it has the intelligence to direct more wind upward (udana) or downward (apana) depending on what’s needed in the moment—hunger (for eating/ingesting) or the urge to empty (for pooping/eliminating). Samana vayu is the lead dance partner with pachaka pitta (the digestive acids in the stomach and small intestine), and we can think of their graceful choreography like the rhythm that creates the rotation of the earth for our day/night cycles, as well as the revolution around our sun for the seasonal cycles.

Now, in the month of the spring equinox, we can appreciate a “balancing” point in that dance that’s also, inevitably, a tipping point toward more sun (in the northern hemisphere). Seasonal transitions are always a good time to tend to agni with extra care, since the volatility in the elemental transfer makes us more vulnerable to imbalances. In particular, the increasing external light will cause our internal digestive capacity to wane through the summer. Hence the recommendation to increase heat and dryness—the main gunas of agni/fire—in spring, which we’ll incorporate into our movement through strengthening poses, balance work, breath work, and dynamic pacing.

In Ayurveda school, the lessons on the srotamsi marked a distinct leveling up of our studies. Everything we learned until that point—the elements, the doshas, even the seven dhatus—was pretty easy to digest, even if the new language felt foreign on the tongue and in the brain. I remember diligently studying my srotamsi flashcards in preparation for our quiz on the topic, abandoning any hope of developing a mnemonic for the 13 +1 channels and conceding to the fact that I’d just have to memorize these words and body parts. There was one thing in particular I had to keep going over—that this srotas I’m discussing, purishavaha srotas, was not purushavaha srotas.

Having worked in publishing for over 10 years, I have more than the average amount of awareness of (and PTSD over) mistaking even one letter (or, God forbid, a comma) in a word or sentence. But in this case, the swapping purisha for purusha was more than just a typo: the former means feces, whereas the latter means the supreme consciousness.

While the philosophy that names the supreme consciousness is not a religion, I still felt it would be grossly offensive to mistake an entity that’s pretty close to God for…well, poop. I’ve managed to keep them straight all these years, but as I sat down to write this (and double checked my spelling), I started to wonder if there wasn’t something to the proximity of these Sanskrit words.

As far as I know, purisha and purusha share no etymological root. But I’m going to venture an interpretation—based on their role in our human experience—that brings them closer than what might feel comfortable. According to Samkhya philosophy, Purusha, as pure spirit/consciousness, desired to have a more sensory experience of itself, and so formed the material world, known as Prakrti. From there spawned what we know as life on earth—individual consciousness, the mind and its aspects, and the matter that we interact with through the five senses. Essentially, all the stuff that, once we digest it in some form or another, comes out as our poop. If Purusha is “the spirit that is hidden in the body,” then the purishavaha srotas is what extracts that spirit—and gets rid of everything else that’s not-spirit. Yes, it’s true that spirit lives in the heart, but it will never get up to the heart if vata and prana are trapped from not pooping. Similarly, while we spend our lives excreting waste that decays and composts into new life, so, too, will our entire body become similar fertilizer—our spirit extracted upon death as we return to “five elemental-ness.”

It is through the end-most phase of our material selves that we return to the beginning of our Self—the being whose desire to feel created all of this. Who loved itself into life.

While beginnings and endings are juxtaposing and overlapping all the time, from a seasonal perspective March is the embodiment of this remarkable, vital, and uncomfortable transfer of power. Strong, invisible vata is at the end of its reign, and it’s not going out without a fight—the big winds, erratic weather, and frenetic energy are like a last hurrah before it poops out. On the other side of vata is kapha season—the infantile stage of the year. Babies are soft, cute. and cuddly to be sure, but they have their own remarkable power. All bundled up in that tiny package are a lot of noise, a lot of feelings, and a lot of poop. While in many ways vata and kapha seem opposite, like purusha and prakriti (and purisha), they’re not so different in other ways. When a life ends, the exit of spirit from the body is as impactful as the arrival of spirit into the body at conception and birth. Prana makes itself known in the first gasp, and in the last. And though it’s going in opposite directions, it’s still the same Prana. This cycle of life is not only subtle, but gross. What we take in as food is grown with the help of someone’s fertilizer. And so the quality of our nourishment depends on quality poop somewhere along the line. Another’s waste becomes, well, our entire being. No wonder the space in our bodies for this process is so big.

Prana acts not only as subtle nutrition in our individual purishavaha srotas—it’s also lending its cosmic intelligence to our place in the interbeing of our existence, that which is connected by poop and all that springs from it. If you scroll back up, you’ll see that one of the functions of this srotas is “strength,” which seems a bit odd given the fact that the channel is mostly about excretion, not “building” as one typically thinks of strength. But remember the colon’s great, almost shocking capacity to hold feces. Ideally, the colon is emptied every day as a sign of good overall health. In this state, our Prana is keyed into the fact that we’re safe, we’re in a place where we can eliminate and be able to replenish our energy with more food afterward.

But what happens when we don’t feel that security? It may or may not have to do with access to food (a fear our bodies wisely developed way back when, but is still a reality for many people today); any amount of stress—vata aggravation—can send a signal to the purishavaha srotas that it might be best to hold onto that weight, that density, that fullness for a little while longer. This is why constipation happens—the body doesn’t want to let go of what it knows it has; it doesn’t want to empty. (Another expression of “balance” we might be apt to explore in spring—where we “hold” still before deciding to release.) The lungs, which remember are paired with the colon, hold emotion similarly in the form of grief. When loss of any kind (of a person, a job, a sense of self) produces a space in our world, the lungs grip and fill with fluids. When faced with the prospect of being alone, the body won’t take the risk of making us emptier on the inside.

March, and spring, can elicit a similar situation as we transition from a season of endings to a season of beginnings. While Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is typically seen in winter—as things die and get dark—it can also arise in the spring, since seeing the rebirth of nature reminds us of our own mortality. Fertilizer will allow nature at large to be reborn again and again (though individual deaths do occur, of course), but even if we have a whole life of excellent poops we won’t escape becoming fertilizer ourselves. That is, if we’re only concerned about the life of the material body. Because the spirit inside that body, inside that poop, can never be eliminated. The better our bodies function, though—i.e., the better we poop—the more time we have to spend with our spirit in this form, and do what we need to do to refine it and get closer to Purusha. The more time we spend loving the life we were given, in a state of ease and relaxation that allows for good poops, the more we are honoring that original divine love that gave us the ability to feel all matter, even waste.

I cannot blame my child-self for her frustration with crowded birthdays. It was important for me then—as it is for all of us—to be able to distinguish myself as an individual worthy of her own spotlight. And now, moving into a new season of life—middle age!—I find that being surrounded by, enmeshed in, others’ lives and loves is an even more valuable gift and validation of my life. Especially since many of those people with whom I used to celebrate are no longer alive. It feels cruel at times that I have to face the years ahead of me without them, until I remember that that’s the whole point. Even when we leave and return to five-elementalness, parts of us always stay around and find ways to spring back into life. The lotus that blooms out of the muddy water. The purusha inside the purisha, that whispers to us, “let go, let go,” over and over, every day, so we can hold onto, give life to, our immortal spirit.

I came across a ritual not too long ago that’s helped me make peace with this reality, and infuse new meaning into my birthday: I now make a point to celebrate and thank my mother on the day I was born. It was her desire—her love for my father, and her desire for my existence—coupled with careful digestive choices (though I apparently caused her a good amount of grief; sorry, Mom!) that created me. And the moment she pushed me out of her safe, warm, nourishing womb, another collision of endings and beginnings occurred. She let go of being a mere woman in order to transform into a mother, my mother; the single body we shared split, and our heart, food, and prana became plural.

She loved me into being, and loved me enough to let me go.